Bible John: The Ballroom Killer

October 30th, 1969. Two sisters leave a Glasgow dance hall with two men they just met. One sister gets dropped off safely at George Square. The other continues on in that taxi, listening to her companion quote Bible verses and condemn adultery. By morning, she'll be dead in her own backyard, strangled with her own stockings. And the man who killed her? He'll become the most famous unidentified suspect in Scottish history. His name was John. At least, that's what he said.

THE ENDURING MYSTERY OF BIBLE JOHN: GLASGOW'S MOST INFAMOUS UNSOLVED MURDERS

When Thursday Night Dancing Turned Deadly

Let's talk about Glasgow in the late 1960s, because you need to understand this city to understand why these murders happened the way they did. While London and San Francisco were doing their whole flower power thing, Glasgow was still very much a city of smog-covered tenements, public washhouses, and working-class struggle. The social scene wasn't sit-ins and love-ins. It was dance halls.

And the king of all dance halls was the Barrowland Ballroom. This place had a neon sign you could see from blocks away, a spring-loaded wooden floor designed specifically to make dancing more fun, and a reputation. Thursday nights at the Barrowland had a very specific clientele. Married people looking for what you might call extramarital entertainment. Women would take off their wedding rings before they even left the house. The whole thing operated on discretion and denial.

This matters because it tells you something about the killer's mindset. He didn't stumble into the Barrowland randomly. He chose Thursday nights at a venue known for married women seeking temporary anonymity. He was hunting a very specific type of victim. Women he could judge. Women he thought deserved what was coming.

Three Women Who Never Made It Home

Between February 1968 and October 1969, three women died after nights at the Barrowland. All brunettes. All between 25 and 32 years old. All mothers. All strangled with their own stockings and left partially clothed near their homes or in public view.

Patricia Docker came first. Twenty-five years old, a nurse. She went to the Barrowland on February 22nd, 1968. Her body was found the next day in a lane near her home, beaten and strangled.

Jemima MacDonald was next. Thirty-two, murdered on August 16th, 1969. Her body was discovered in a derelict tenement building. Several people had seen her at the Barrowland that night, dancing with a tall, well-dressed man in his late twenties with reddish hair.

Then came Helen Puttock. Twenty-nine, mother of two. October 30th, 1969. She went dancing with her sister Jean and met two men. They all left together, caught a taxi, and Jean got dropped off at George Square with her dance partner. Helen continued on with the man who called himself John. By the next morning, Helen was dead in the back courts near her home.

Police decided these three murders were connected. Same location. Same victim type. Same method. They created the narrative of a serial killer prowling the Barrowland. And maybe they were right. Or maybe they were under so much pressure to consolidate the threat that they forced a pattern. Because years later, Joe Beattie, the detective who led the original investigation, admitted he never had definitive evidence linking all three murders to one person.

The Taxi Ride That Named a Killer

Jean Langford gave police the only detailed description of the killer they would ever get. During that taxi ride from the Barrowland, she sat in the back seat with Helen and the man named John. And John talked.

He quoted the Bible. Repeatedly. He went on about adultery and how married women shouldn't be in dance halls. The whole performance was so over-the-top moralizing that when Helen turned up dead hours later, the press immediately dubbed the killer Bible John.

Jean described him as 25 to 30 years old, about six feet tall, with light reddish hair, blue-grey eyes, and a smart, modern appearance. She said he was well-spoken, better dressed than the typical Barrowland crowd. He seemed like he didn't quite belong there, which is probably exactly why he chose that venue. He could blend in just enough while maintaining his superiority complex.

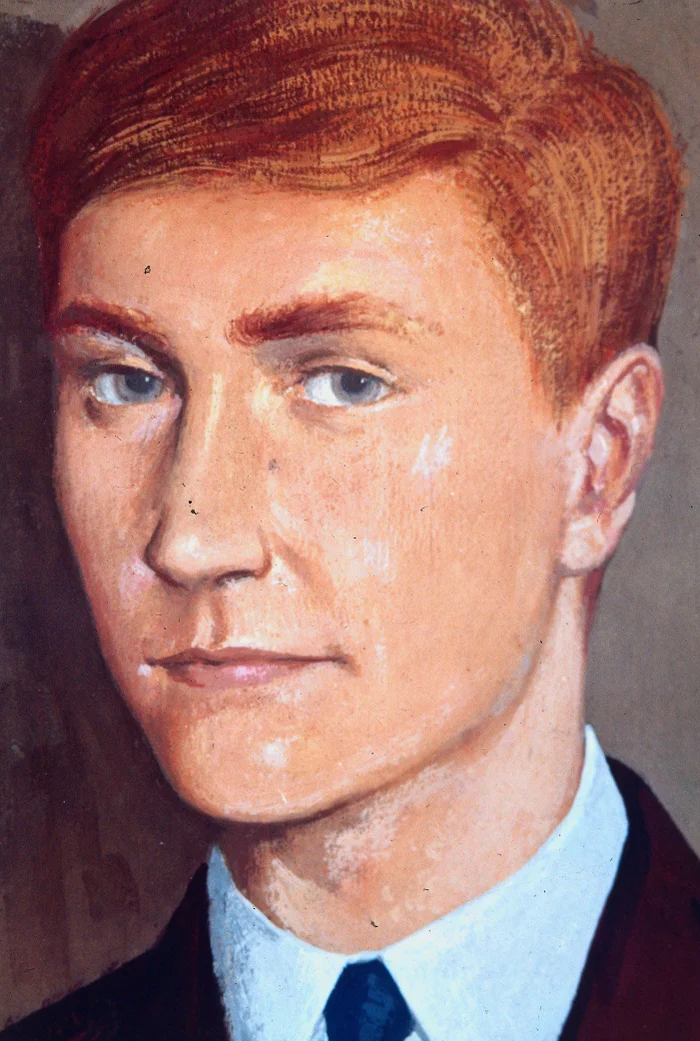

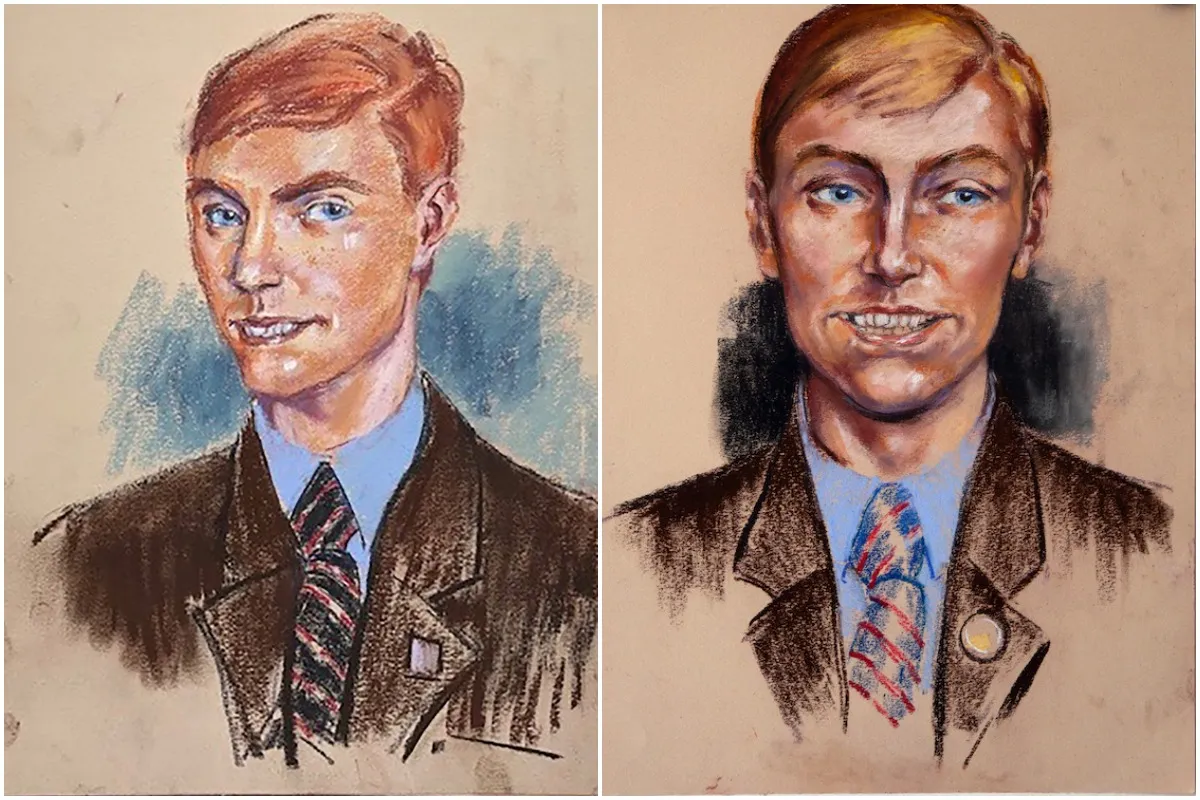

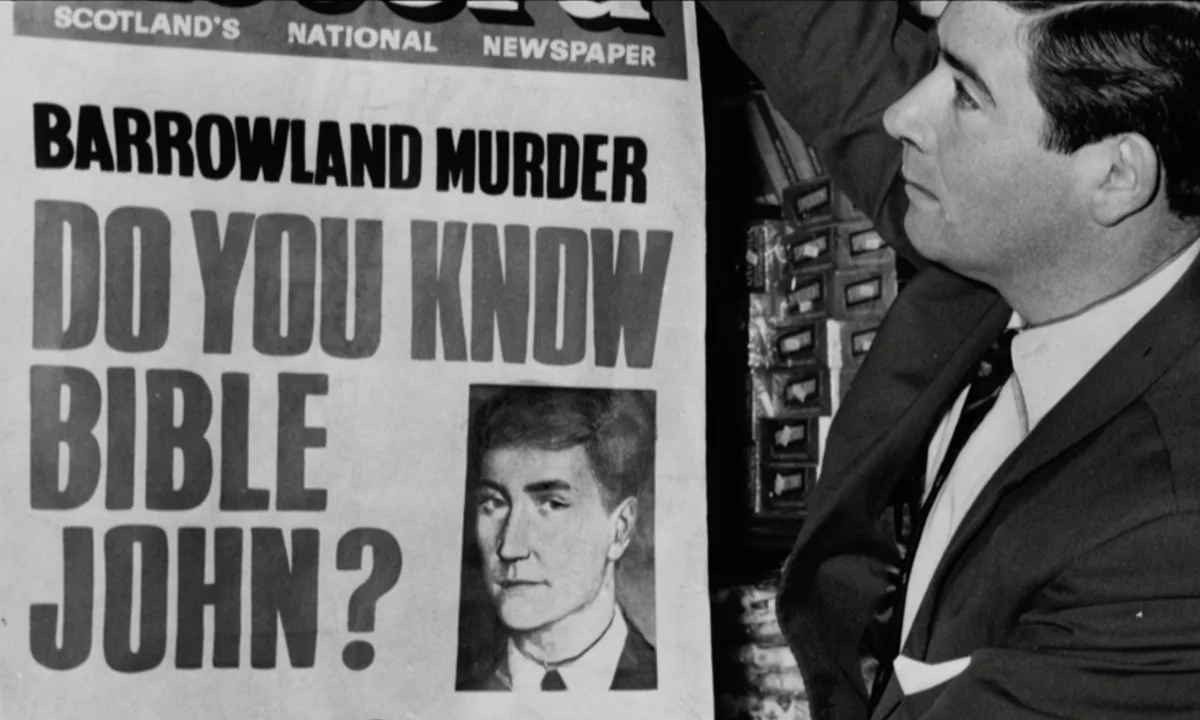

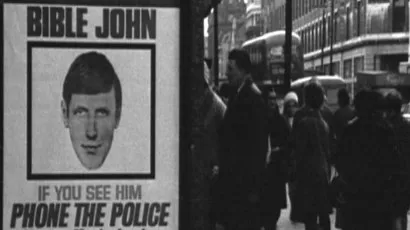

Based on Jean's description, police commissioned Scotland's first-ever composite sketch of a murder suspect. An artist from the Glasgow School of Art created a drawing that's been called Scotland's Mona Lisa. Narrow eyes. Unreadable expression. That image got plastered everywhere.

Police interviewed 5,000 people. Took 50,000 statements. Followed every lead. And caught nobody.

The Problem With One Perfect Witness

Here's the thing about having such a vivid profile. It can work against you. Police became so focused on finding a red-haired, well-spoken, Bible-quoting man that they might have missed other suspects entirely. When you've got a witness as certain as Jean Langford and an image as striking as that composite sketch, it's easy to start seeing what you expect to see.

And there's another layer. The original investigation was soaked in misogyny. The press and public spent time questioning why these women were out dancing in the first place, why they were seeking affairs. The focus kept sliding from the killer's actions to the victims' supposed moral failings. Which is exactly what the killer would have wanted. His whole thing was judgment and punishment.

When DNA Was Supposed to Solve Everything

Fast forward to the 1990s. DNA testing was becoming the miracle technology that would solve cold cases everywhere. Police had biological evidence from Helen Puttock's murder scene. A semen stain. Hair samples. Material that could theoretically identify the killer decades later.

The problem was degradation. The samples were old, poorly preserved. The technology wasn't quite up to the task yet.

Enter John Irvine McInnes. This man became the prime suspect, and allegations emerged that he'd been protected during the original investigation because he was the cousin of a senior police officer. When McInnes died by suicide in the 1980s, those allegations only intensified.

In 1995, police exhumed McInnes's body for DNA testing. The results came back inconclusive. Not a match, but not a definitive exclusion either. The Crown officially cleared McInnes in 1996, but people believed there was a cover-up. Conspiracy theories exploded.

It took until 2005 for advances in DNA technology to finally, definitively exclude McInnes. His DNA did not match the profile from Helen Puttock's murder scene.

The Serial Killer Who Couldn't Have Done It

By then, a new suspect had emerged. Peter Tobin. Convicted serial killer and rapist. He was the right age. He'd been in Glasgow around the right time. His known crimes involved similar violence. Criminologists started pushing the theory that Bible John was definitely Peter Tobin.

There were problems. Multiple problems. First, DNA testing definitively ruled him out. His genetic profile didn't match the biological evidence from the Puttock crime scene.

Second, and this is the part that really kills the theory, Tobin had an airtight alibi for the last two murders. He married his first wife in Brighton on August 6th, 1969. That was ten days before Jemima MacDonald's murder on August 16th. Marriage certificate proves it. He was still living in Brighton on October 30th when Helen Puttock was killed. He would have had to travel back to Glasgow without his new wife knowing, commit murder, and get back to Brighton. The timeline doesn't work.

So Tobin could have theoretically killed Patricia Docker in February 1968 before he moved to Brighton. But he's forensically excluded from Helen Puttock's murder, and he has a documented alibi for being in another city during the other two. Some people still think he was involved. The science and the timeline say otherwise.

When a Podcast Forces Action

In late 2022 and early 2023, journalist Audrey Gillan released a BBC podcast called Bible John: Creation of a Serial Killer. The series focused on the victims as real people. It tore apart the misogyny that defined the original investigation. And it brought the John Irvine McInnes cover-up allegations roaring back.

Gillan's podcast claimed that officers involved in the 1995 exhumation were certain of McInnes's guilt despite the inconclusive DNA results, and that police chiefs buried his name because of family connections.

Police Scotland responded in October 2023 by confirming they were reviewing the podcast's claims. Family members of the victims were contacted. Allan Mottley, Jemima MacDonald's son, called it a bombshell and expressed hope that police would finally admit the original investigation was botched.

The fact that a podcast could force a formal police review tells you something. Sometimes outside pressure is the only thing that moves the needle.

The Historian With a New Theory

In 2024, Australian historian Dr. Jillian Bavin-Mizzi published a book called Bible John: A New Suspect. Her suspect is John Templeton, a Glasgow printer who died in 2015. She says she's 100% convinced based on circumstantial evidence.

There's a complication. Templeton was interviewed by police in 1969 right after Helen Puttock's murder. And he was ruled out.

So for this theory to hold, Police Scotland would have to accept that they made a massive mistake in the original investigation and missed the killer when he was sitting right in front of them. That's hard to swallow, especially without definitive DNA confirmation.

Police Scotland confirmed they're investigating the claims in her book. Whether it leads anywhere depends entirely on whether modern forensic technology can extract a usable genetic profile from that degraded 1969 semen stain.

The Only Evidence That Matters

Here's what we know for certain. Someone left biological evidence at Helen Puttock's murder scene. That genetic material represents an unidentified male. Every theory, every suspect, every book and podcast has to answer to that DNA profile.

John Irvine McInnes? Excluded. Peter Tobin? Excluded and alibied. John Templeton? Still under investigation, but he can only be confirmed or eliminated through DNA comparison.

The science is both the barrier and the solution. Investigative genetic genealogy could theoretically identify Bible John. But it requires a high-quality genetic profile. And after fifty-plus years of degradation, nobody knows if that's even possible with the evidence that exists.

What Really Happened at the Barrowland

So where does that leave us? Three women dead. A witness who gave an incredibly detailed description. A composite sketch that became iconic. Decades of suspects who didn't pan out. And a killer who may or may not have been a single person.

Because that's the other possibility. What if Bible John, as we understand him, only killed Helen Puttock? What if the Docker and MacDonald murders were committed by someone else? The lead detective thought it was possible. The pressure to create a unified narrative might have linked cases that shouldn't have been linked.

Bible John has been Scotland's bogeyman for over fifty years. But Patricia Docker, Jemima MacDonald, and Helen Puttock weren't killed by a ghost story. They were killed by a man. A man whose genetic profile still sits in an evidence locker somewhere, waiting for science to finally be good enough to tell us who he was.

Until then, we're left with that composite sketch. Those narrow eyes staring out from cold case files. Scotland's Mona Lisa. A face without a name. A killer without justice.