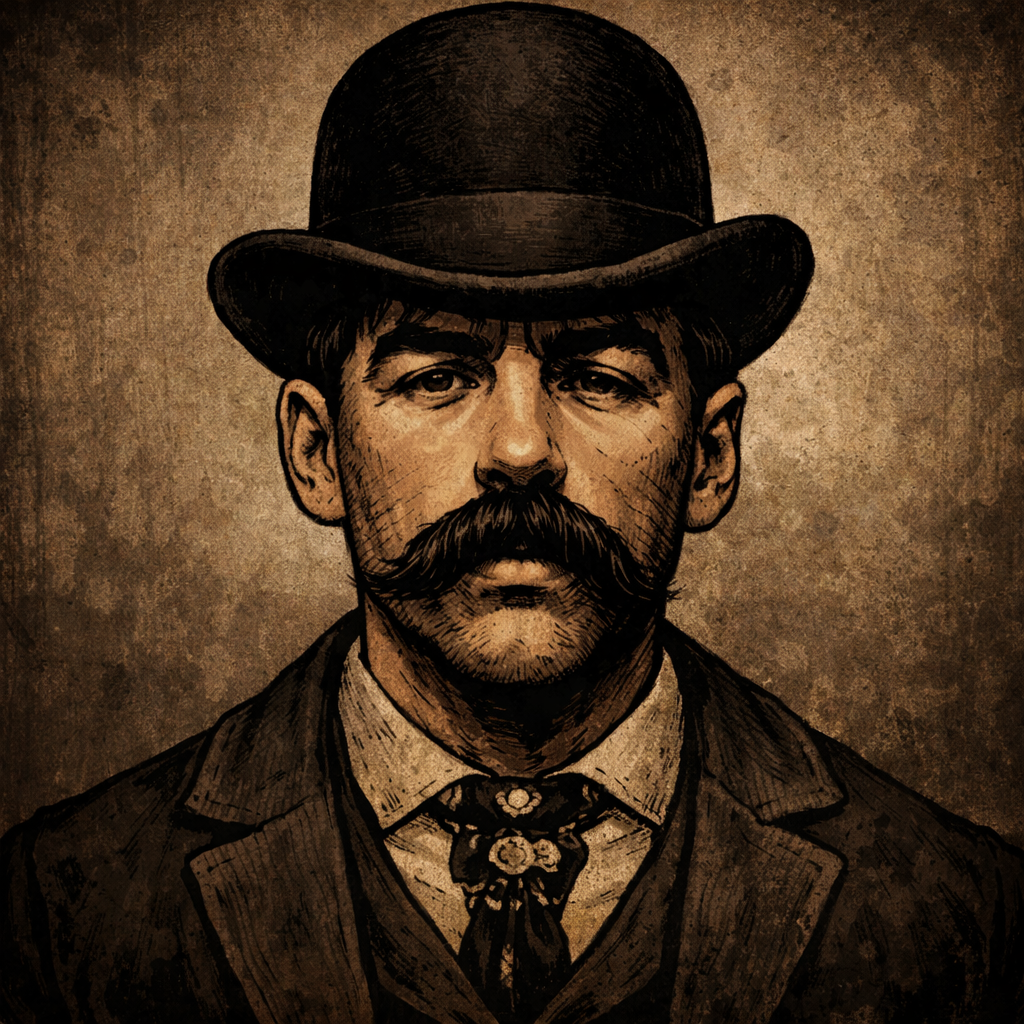

Building a Murder Business: H.H. Holmes and the Industrialization of Death

There's this assumption that serial killers are driven by compulsion. By sexual sadism or rage or psychotic delusions. That they're fundamentally broken in a way that makes them kill. But what if I told you about someone who started out as a straightforward con artist, running insurance scams and frauds, and sort of drifted into murder because it was more efficient than the cons? That's H.H. Holmes. He had a business problem, and murder became his solution. This is True Crime Blueprint.

The Economics of Death

Before we get into who Herman Webster Mudgett became, we need to understand what he was trying to do. This is 1880s America, and the country is building systems faster than it can secure them. Life insurance is becoming standardized, but companies in different states don't talk to each other. Railroads mean you can be in three different cities in a week using three different names. The postal service is expanding, but there's no way to verify who's actually sending letters.

Herman Mudgett looked at all of this and saw opportunity. Opportunity to make money. When he enrolled at the University of Michigan medical school in 1882, he was already running minor cons. He'd take out small loans using fake names, buy things on credit and skip town. Standard grifter stuff. But medical school introduced him to something new: the cadaver trade.

Medical schools needed fresh bodies for dissection. Legal sources were limited. So there was this whole underground market for corpses. Mudgett got involved, and somewhere in that process, he had a realization. A dead body was a commodity. It had value. And more importantly, it could represent anyone you claimed it was.

His first insurance fraud was almost elegant in its simplicity. He'd take out a life insurance policy on a person who didn't exist, then acquire a cadaver, disfigure it enough to make identification difficult, and report the death. The insurance companies would pay out, and he'd disappear with the money. This is 1884. There's no fingerprint database, no forensic dental records, no system for verifying claims across state lines.

He was making money, and nobody was getting hurt. At least not yet.

The Shift from Fraud to Murder

When does a con artist become a killer? With Holmes, it's hard to pinpoint exactly when the line got crossed, but we know that by the time he arrived in Chicago in 1885, something had changed. He'd renamed himself Dr. H.H. Holmes, established himself as a pharmacist, and started acquiring property and businesses. And people who got in his way started disappearing.

Mrs. Elizabeth S. Holton owned a pharmacy in Englewood. Her husband had recently died, and she needed help. Holmes came in as an assistant, charmed her, learned the business. Within months, she was gone. Holmes told people she'd moved to California. Nobody investigated. Holmes now owned a pharmacy.

This became the pattern, and here's what's interesting about it from a criminal psychology standpoint. Holmes was killing because these people had assets he wanted, and removing them was more efficient than convincing them to hand those assets over. There's no evidence of sexual assault with his victims. No ritualistic behavior. No keeping of trophies in the traditional sense.

Julia Smythe worked as a clerk at his pharmacy. She was married, had a daughter named Pearl. Holmes seduced her, got her pregnant, performed an abortion that likely caused complications. When Julia and Pearl became inconvenient, they disappeared. Minnie Williams inherited valuable property in Fort Worth, Texas. Holmes romanced her, convinced her to sign the property over to him, and then killed her and her sister Anna when they came to visit.

This is the part that makes Holmes different from almost every other killer we talk about on this show. He's solving business problems. People have things he wants. The most efficient path to getting those things involves their death. So they die.

Building the Infrastructure

Between 1887 and 1892, Holmes constructed his three-story building at 63rd and Wallace in Englewood. And I need to be really clear about what this building actually was because the newspapers of the era, and honestly most retellings since, have turned it into this Gothic nightmare castle with hundreds of rooms and torture chambers.

What Holmes built was a processing facility. The first floor had legitimate retail space. The pharmacy, some shops. That's where money came in. The second floor had apartments where he could house employees and women he was courting. That's where he maintained control over people. And the third floor was supposed to be a hotel, though it was never actually completed. That was the future expansion of the operation.

The hidden features tell you what this building was really for. Holmes constantly changed contractors during construction. He'd hire someone to build one section, then fire them and hire someone else. He'd claim there were mistakes, demand changes, refuse to pay. The point was that no single person ever understood the full layout.

The second floor had rooms that could be locked from the outside and soundproofed. There were gas jets Holmes could control from his bedroom to asphyxiate people quietly in other rooms. There were chutes that led from the second floor directly to the basement, so you could move a body without being seen by other tenants.

And the basement was where the disposal happened. There was a dissection table, a furnace large enough to cremate human remains, vats of acid and quicklime for dissolving flesh. Some accounts suggest Holmes had surgical equipment down there, though the exact inventory was never fully documented.

Here's the thing. Holmes had learned in medical school that articulated skeletons had value. Medical schools would pay for them. So he was processing bodies for multiple purposes. The acid would strip the flesh, he'd articulate the bones, bleach them. Whether he actually sold them to medical schools is debated by historians, but the equipment to do so was definitely there.

This was infrastructure. The soundproofing meant he could work without interruption. The gas jets meant he could kill without physical struggle. The disposal system meant he could eliminate evidence efficiently. Target identification happened in the pharmacy. Isolation happened in the second-floor apartments. Execution happened in the soundproofed rooms. Processing and disposal happened in the basement. And throughout all of it, he was generating revenue at every stage.

The Pitezel Scheme

By 1894, Holmes had been operating this way for nearly a decade. And then he reconnected with Benjamin Pitezel, a carpenter and con artist he'd worked with before. Pitezel was good at forgery, good at playing roles in insurance scams. But he was also drinking heavily and becoming unreliable. Holmes decided they'd do one more job together, a big one.

The plan was to defraud the Fidelity Mutual Life Association for ten thousand dollars, which would be over three hundred thousand today. They'd fake Pitezel's death, use a cadaver to stand in for his body, disfigure it to match Pitezel's description, and his wife Carrie would collect the insurance. Then Pitezel would disappear to start a new life somewhere, and they'd split the money.

Except Holmes changed the plan. Because why go through the trouble of finding a suitable cadaver when you could kill Pitezel himself? It was cleaner. Fewer loose ends. On September 2, 1894, in Philadelphia, Holmes killed Pitezel, likely using chloroform, and burned his body with benzine to make it look like an accidental laboratory explosion.

And here's where the con artist fully becomes the monster. After killing Pitezel, Holmes went to his widow Carrie and told her that her husband was alive but in hiding. He said they needed to keep moving to avoid the insurance investigators. Holmes took custody of three of the Pitezel children, Alice, Nellie, and Howard, claiming he was taking them to meet their father in London.

For months, he moved Carrie and her two remaining children through the northern United States and Canada, staying in different cities, always a few days behind the group with the other three children. The kids kept writing letters to their mother asking when they'd see her. Holmes would intercept the letters and write fake replies. He kept everyone separated and confused while he figured out what to do with them.

He killed all three children. They were starting to ask questions about where their father was, and if anyone started investigating, they might be able to identify Pitezel's body. They were loose ends in the fraud scheme, and Holmes eliminated loose ends.

Alice and Nellie were asphyxiated and buried in a basement in Toronto. Howard was killed and his body partially burned in a chimney in Indianapolis. These were the costs of doing business.

The Unraveling

Holmes finally got caught because of a completely different crime. He'd been arrested in St. Louis for a horse theft scheme, and one of his accomplices, Marion Hedgepeth, decided to rat him out. Hedgepeth told police about Holmes' insurance fraud plans, which led investigators to start looking at the Pitezel death more closely.

They realized the burned body in Philadelphia really was Benjamin Pitezel. And once they figured that out, they started wondering where Carrie's three missing children were. The Philadelphia Police Department assigned Detective Frank Geyer to find them.

Geyer's investigation is fascinating because he approached it like you'd approach a financial audit. He started with Holmes' paper trail. Every train ticket. Every rental agreement. Every hotel registry. Holmes had been careful about using aliases and covering his tracks, but he'd also been keeping receipts because he was fundamentally a businessman. He tracked expenses. He documented transactions.

Geyer followed that paper trail across six states, visiting every city where Holmes had stayed. He used newspapers to spread information about the missing children, essentially crowdsourcing the investigation before that was even a concept. And slowly, methodically, he reconstructed Holmes' movements.

In Toronto, a landlord recognized the description and remembered renting to a man with two little girls. Geyer searched the property at 16 St. Vincent Street and found Alice and Nellie's bodies in a shallow grave in the cellar. In Indianapolis, neighbors remembered a boy who'd stayed briefly at a cottage Holmes had rented. Geyer found bone fragments and teeth in the chimney.

The discovery of those children's bodies was what broke the case open. Because Holmes could explain away a lot of things. He could claim Pitezel's death was accidental. He could say the insurance claim was a misunderstanding. But you can't explain away three dead children buried in your rental properties.

The Trial and What It Revealed

Holmes' trial in October 1895 was where his true nature became impossible to deny. He tried to represent himself, which gives you an idea of his ego. He cross-examined witnesses. He challenged the forensic evidence. He maintained that Pitezel had killed himself and that the children had died of natural causes or accidents.

But the prosecution built a timeline that showed exactly how calculated everything was. The life insurance policy purchase. The rental agreements for properties in three different cities. The intercepted letters. The forged correspondence. Every piece of it showed planning and intention.

What's remarkable about the trial is that it revealed how Holmes thought about his crimes. When confronted with evidence, he didn't express remorse or try to claim insanity. He treated it like a failed business venture. He was frustrated that his plans hadn't worked out, annoyed that he'd been caught, but there was no emotional attachment to the victims at all.

The prosecutor described him as someone who'd figured out that murder was profitable and had industrialized the process. That framing is actually really accurate. Holmes had taken something that most people do out of rage or compulsion or psychosis and turned it into a systematic operation with infrastructure and revenue streams.

He was convicted of murdering Benjamin Pitezel and sentenced to death. On May 7, 1896, he was hanged at Moyamensing Prison in Philadelphia. The execution was reportedly prolonged, though accounts vary on exactly how long it took. Holmes had requested that his body be buried in a cement-filled coffin ten feet deep, supposedly to prevent medical schools from dissecting him. Given what he'd done to his own victims, the irony wasn't lost on anyone.

The Business Model of Murder

So what do we actually learn from H.H. Holmes? Because here's what makes him different from almost every other case we've covered. Most serial killers have a compulsion. They're driven by sexual sadism or a need for control or voices in their head. Their crimes follow patterns because they're fulfilling psychological needs.

Holmes was running a business. The victims were whoever had something he wanted or whoever became inconvenient to his operations. Sometimes that was women with property. Sometimes it was business partners who knew too much. Sometimes it was children who might identify a body.

The methods varied too. Some victims were poisoned. Some were asphyxiated. Some were chloroformed. Holmes used whatever was most efficient for the situation. The building in Englewood was infrastructure. The soundproofing meant he could work without interruption. The gas jets meant he could kill without physical struggle. The disposal system meant he could eliminate evidence efficiently.

And critically, he was always generating revenue. The pharmacy was legitimate income. The fraudulent insurance claims were significant payouts. The property he inherited from victims got resold. Every aspect of his operation had a financial component.

This is what makes Holmes so disturbing to criminal psychologists. We understand rage killers. We understand sexual sadists. We understand psychotic breaks. But Holmes represents something different. He represents someone who figured out that killing people could be profitable and approached it with the same mindset someone else might bring to opening a restaurant or running a factory.

The Exploitation of Progress

The other thing that makes Holmes significant is timing. He was only able to operate the way he did because America was building systems faster than it could secure them. The life insurance industry was expanding rapidly, but companies couldn't verify claims across state lines. Railroads meant you could be mobile and anonymous in a way that was impossible before. Cities were growing so fast that traditional community oversight broke down.

Holmes identified vulnerabilities in modern systems and exploited them. The insurance fraud worked because there was no central database. The property schemes worked because title transfers weren't well-regulated. The murders worked because urban anonymity meant people could disappear without immediate alarm.

In a weird way, Holmes' crimes forced these systems to evolve. After his case, insurance companies developed better verification procedures. Police departments started sharing information across jurisdictions. The concept of using forensic evidence to prove crimes became standard practice.

Detective Geyer's investigation showed that you could track someone across multiple states if you were methodical and persistent. The use of dental evidence to help identify Howard Pitezel's remains contributed to forensic dentistry becoming a legitimate tool. The multi-state cooperation between Philadelphia, Boston, Chicago, Toronto, and Indianapolis police set a precedent for how to handle criminals who crossed jurisdictional lines.

The Legacy of the Murder Entrepreneur

When the FBI's Behavioral Science Unit started developing profiles of different killer types in the 1970s, they created a category for the profit-motivated killer. That category exists largely because of H.H. Holmes. He demonstrated that serial killers can make calculated business decisions rather than acting purely on compulsion.

This changes how you investigate them. A compulsion killer has patterns you can predict. They have types they target. They have methods they prefer. But a profit killer can be completely opportunistic. Their victim pool is whoever becomes financially valuable or operationally inconvenient. Their methods are whatever works for the situation.

Holmes' confirmed victim count is probably somewhere between nine and twenty-seven, though the exact number will never be known. Some bodies were completely destroyed. Some people who disappeared were probably his victims but can't be definitively linked. The newspapers claimed over two hundred victims, which was almost certainly exaggeration designed to sell papers. Even Holmes himself gave conflicting numbers in his various confessions.

But the number almost doesn't matter because what makes Holmes significant is the mindset. He proved that someone could approach murder as a business opportunity and build infrastructure around it. That was new. That changed how law enforcement had to think about motive and methodology.

The 2017 Confirmation

For over a century, there were rumors that Holmes had somehow escaped execution. Some people claimed he'd bribed officials and fled to South America. The fact that he'd been buried in cement ten feet deep fed the conspiracy theories. In 2017, his great-great-grandson Jeff Mudgett and the History Channel funded an exhumation to settle the question.

A forensic team from the University of Pennsylvania opened the grave and found that the cement casing had actually preserved the remains remarkably well. His clothing was largely intact. His mustache was still visible on the skull. Dental records matched prison medical records showing distinctive dental work. DNA extracted from tooth pulp matched living descendants.

Herman Webster Mudgett, Dr. H.H. Holmes, the murder entrepreneur, was executed on May 7, 1896, exactly as the records said. The conspiracy theories could finally be put to rest.

Understanding What We're Looking At

H.H. Holmes looked at America's rapid modernization and saw ways to profit from the chaos. The country was building amazing infrastructure, creating new industries, developing systems that connected people across vast distances. Holmes figured out how to weaponize all of it.

When we build systems, we create vulnerabilities. When we create anonymity, some people will use it to disappear, and others will use it to make people disappear. When we prioritize efficiency and profit above everything else, we sometimes create environments where the most ruthless people thrive.

Holmes became a killer because it made sense within his worldview. People were resources. Death was a tool. Profit was the only thing that mattered. And for almost a decade, in the middle of America's greatest celebration of progress and modernity at the 1893 World's Fair, that worldview let him build a business model around murder.

The White City celebrated what humanity could build. The building in Englewood showed what humanity could destroy. Both existed in the same city, at the same time, because progress and predation have always been two sides of the same coin. Holmes understood that better than most, and he exploited it until Detective Frank Geyer patiently, methodically, followed the paper trail and found those three children.

In the end, Holmes was caught because he was a businessman who kept records. The same organizational skills that made his murder operation efficient also created the evidence trail that led to his conviction. That's the real irony of H.H. Holmes. He was undone by the very thing that made him successful.