The Feral Child Who Became Florida's Deadliest Serial Killer

In 1952, nurses at a Schenectady orphanage discovered a six-month-old baby in such horrific condition that most believed he was beyond saving. One nurse refused to give up on him. Her love and dedication should have been enough to heal the trauma. But sometimes, even the most well-intentioned rescue can't rewrite a story that's already been written in pain.

The Abandoned Child Who Defied the Odds

The year was 1952 in Schenectady, New York, when staff at a local orphanage opened their doors to find someone had left them a baby. Six months old, this wasn't unusual for the time. What was unusual was the condition this child was in.

Paul Zeininger was the fourth of five children born into the Zeininger household, and like his siblings, he'd ended up in state care. But Paul's situation was different. This baby had been through something that left even experienced medical professionals shaken.

The Reality of Early Trauma

When Paul arrived at the orphanage, he could barely speak. His developmental delays were severe, and he'd created a survival mechanism that horrified the staff. Accustomed to long periods without food, he'd begun eating his own feces to survive. The doctors and nurses were unanimous in their assessment: this child needed specialized care that the average foster family couldn't provide.

The medical team recommended Paul remain in institutional care indefinitely. They believed his trauma was too extensive, his needs too complex for traditional adoption. But one person refused to accept that recommendation.

Norma Stano was a nurse, and she saw something in this malnourished, traumatized baby that others couldn't. Together with her husband Eugene, she spent six months fighting the system for the right to adopt Paul and raise him as their own child.

A Love That Should Have Been Enough

The battle was fierce. Medical professionals argued against the placement, concerned that even Norma's nursing background wouldn't be sufficient for Paul's extensive needs. But the Stanos persisted, and eventually, they won.

Reluctantly, the orphanage staff placed Paul in Norma and Eugene's care. They changed his name to Gerald Stano, hoping to distance him from his traumatic past and give him a fresh start with a loving family.

By every measure that mattered, Norma and Eugene were exemplary parents. They provided Gerald with stability, consistent meals, medical care, and genuine affection. They created the kind of home environment that should have been transformative for a child who'd known only neglect and abuse.

When Love Meets Lasting Damage

But Gerald's past had left marks that love alone couldn't erase. Despite his parents' efforts, he continued struggling to catch up with his peers developmentally and socially.

At ten years old, Gerald was still wetting the bed regularly. His classmates were merciless. Boys would physically assault him, while girls would mock him and call him names. Gerald later claimed this pattern of humiliation and rejection by women continued well into his adulthood, describing incidents where women would insult him, pull his hair, and even throw beer bottles at him.

Academically, Gerald remained behind his age group. His grades never rose above Cs and Ds in most subjects. He showed aptitude in only two areas: music and track and field. But even his success in track came with a troubling revelation.

Eugene discovered that Gerald had been stealing money from his wallet repeatedly, using the cash to bribe other students to let him win races. This behavior revealed something concerning about Gerald's relationship with achievement and honesty.

The Descent Begins

As Gerald entered adolescence, his behavioral problems intensified rather than improved. At fourteen, while still enduring bullying from classmates, he began expressing his frustrations in increasingly destructive ways.

His first arrest came for setting off a false fire alarm. The second followed shortly after, when police caught him throwing rocks at passing cars from a highway bridge. These weren't typical teenage pranks; they demonstrated a concerning pattern of behavior that seemed to escalate with each incident.

Gerald's academic struggles continued, and he didn't graduate high school until age twenty-one. Through Norma's connections, he secured a job at a local hospital, but his employment was short-lived. Colleagues discovered he'd been stealing from them, and Gerald was terminated.

The Move to Florida and a Critical Moment

Hoping a change of environment might help their son, the Stanos relocated to Florida. Unfortunately, Gerald's pattern of job loss continued. Whether due to theft, chronic tardiness, or other workplace issues, he couldn't maintain steady employment.

Then Gerald crossed a line from which there was no return. He was caught sexually assaulting a mentally disabled young woman who lacked the capacity to consent. The situation became more complicated when the victim discovered she was pregnant.

Once again, Norma and Eugene stepped in to help their son. They paid for the woman's medical expenses, including an abortion, effectively shielding Gerald from the full consequences of his actions.

This intervention taught Gerald a lesson that would prove catastrophic: that his actions didn't necessarily have consequences, especially when his parents were willing to protect him from them.

The Beginning of a Killing Spree

Years would pass before the full scope of what Gerald had learned from that lesson became clear. In spring 1980, a woman named Donna Hensley walked into a Florida police station, barely alive and clearly traumatized.

Donna worked as a prostitute, and she'd agreed to accompany a client to a hotel room about a week earlier. What should have been a straightforward transaction turned into a near-death experience.

According to Donna's statement to police, an argument erupted over her services. When she attempted to leave, the man attacked her with brutal violence, stabbing her thirty times before screaming an insult and fleeing the scene.

Donna's survival was nothing short of miraculous. Despite her extensive injuries, she managed to make her way to authorities and provide them with crucial information: the attacker's license plate number, a description of his vehicle, and most importantly, his name.

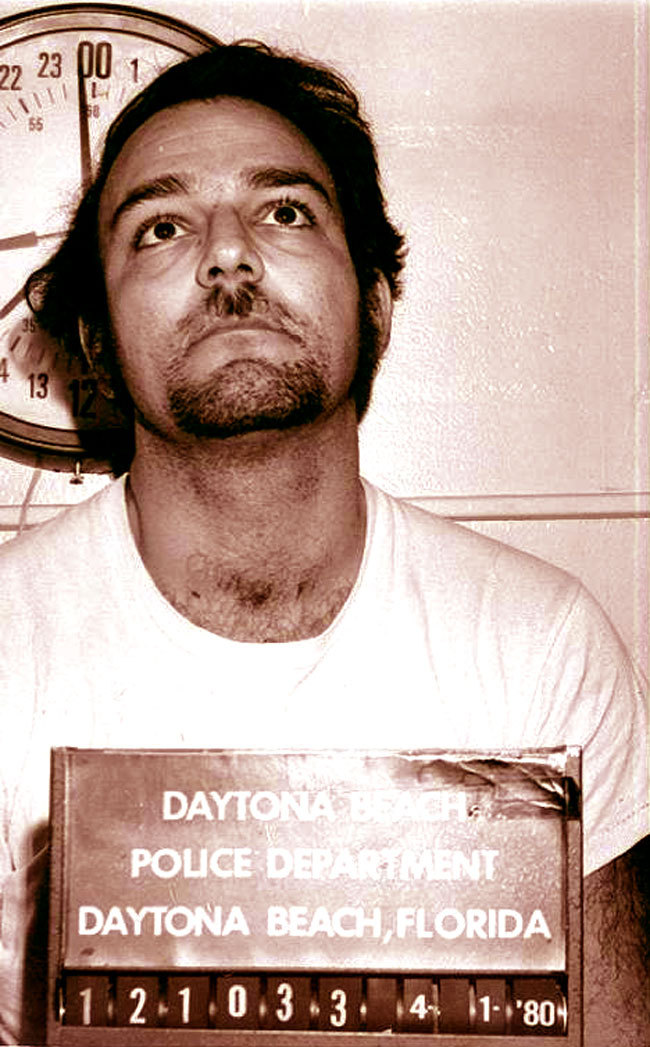

Gerald Stano.

The Investigation Unfolds

Police discovered that Gerald was well-known among local sex workers, though none had previously reported him for violence or mistreatment. With Donna's evidence, however, authorities had enough to arrest Gerald for attempted murder.

While Gerald sat in jail awaiting trial, two college students made a grim discovery near Daytona Beach Broadwalk. They found the decomposing remains of twenty-year-old Mary Carol Maher, who had been stabbed multiple times in her back, legs, and chest.

Given that police had a suspect in custody for a nearly identical stabbing attack on another woman, investigators approached Gerald about Mary's murder. Initially, he denied involvement, admitting only that he'd seen Mary before.

Then something broke inside Gerald. He confessed to killing Mary Maher and provided investigators with detailed information about how he'd committed the murder. He even led them to where he'd left her body, confirming details only the killer would know.

A Flood of Confessions

Mary Maher's murder confession opened the floodgates. Gerald began admitting to killing woman after woman throughout Florida. Initially, he claimed his killing spree began in the 1970s when he was in his early twenties. Later, he revised this timeline, admitting he'd actually started murdering women in the 1960s when he was eighteen years old.

Gerald's final confession count reached forty-one murders. Investigators could definitively connect him to twenty-three of these cases, though they believed the actual number of his victims could be as high as eighty-eight women.

The scope of Gerald's crimes was staggering. One victim remained unidentified for forty-three years until genetic genealogy finally revealed her identity in 2024, demonstrating the lasting impact of his violence on families and communities.

Leading Police to the Truth

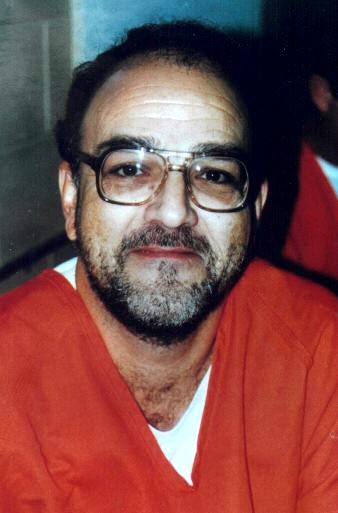

For six years following his initial confession, Gerald continued working with investigators, leading them across Florida to locations where he'd attacked and disposed of his victims. Detective Paul Crow, who headed the investigation, observed Gerald's behavior throughout this process.

According to Detective Crow, Gerald showed emotion only once during their extensive travels to crime scenes. This occurred when they visited the location of his final victim, where Gerald wept. However, Crow believed Gerald's tears were for himself, mourning his lost freedom rather than expressing genuine remorse for his actions.

The Final Reckoning

At trial, Gerald was convicted of nine murders and received three death sentences. His case moved through the appeals process for years before reaching its conclusion in spring 1998, when he was scheduled for execution by electric chair.

In his final moments, Gerald attempted to recant all his previous confessions. "I am innocent," he declared. "I am frightened. I was threatened, and I was held month after month without any real legal representation. I confessed to crimes I did not commit."

He specifically blamed Detective Paul Crow for coercing false confessions from him. However, many people, including family members of two victims who witnessed his execution, believed the state was executing the right man.

The Lasting Questions

Gerald Stano's case raises profound questions about the nature of trauma, intervention, and redemption. Here was a child who experienced unthinkable abuse, was rescued by loving parents, and received care that should have been transformative.

Norma and Eugene Stano did everything society tells us should work. They provided stability, love, medical care, and endless second chances. They fought systems and spent their resources trying to help their son become a productive member of society.

Yet their love and dedication couldn't overcome the damage that had been done in Gerald's first six months of life, nor could it prevent him from learning that actions might not have consequences if the right people were willing to shield him from them.

Gerald's story doesn't diminish the importance of intervention and support for traumatized children. Rather, it illuminates the complex realities of severe early trauma and the limitations of even the most well-intentioned efforts to heal it.

The women Gerald killed deserved better than to become casualties in a story that began with one baby's abandonment in 1952. Their lives had value that extended far beyond their role in Gerald's narrative, and their families continue to live with the consequences of his choices decades later.

Some stories don't have redemptive endings, no matter how much love and effort goes into trying to create them. Gerald Stano's life serves as both a testament to the resilience of the human spirit in people like Norma and Eugene, and a sobering reminder that some damage runs too deep for any intervention to fully repair.