The Shadow of the Adirondacks: Robert Garrow and the Lawyers Who Kept His Deadly Secrets

Today's story takes place in the summer of 1973, deep in the Adirondack Mountains of New York. Four young campers went into the woods. Only three came back. The man responsible would spend years convincing doctors he couldn't walk, escape prison inside a bucket of fried chicken, and die in the brush with a hit list in his cell. And two lawyers sat on secrets that rewrote American law. This is the story of Robert Garrow.

Robert Garrow and the Adirondack Murders: The 1973 Case That Rewrote American Legal Ethics

There's a summer the people of the Adirondack Mountains have genuinely never gotten over, and most of the country never even knew it was happening.

It's 1973. Watergate is consuming everything. Nixon is sweating through press conferences while his entire administration unravels in real time, and most of America is watching from their living rooms. But while that noise was filling every airwave, something much quieter and far more terrifying was building in the forests of upstate New York.

Who Was Robert Garrow? A Dannemora Childhood Defined by Violence

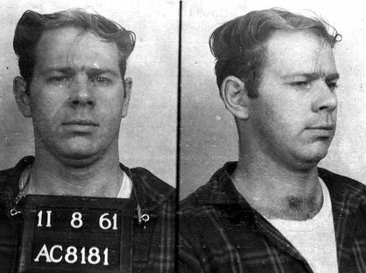

Robert Garrow was born on March 4, 1936, in Dannemora, New York, a tiny North Country town that sits directly alongside the Clinton Correctional Facility, one of the most formidable prisons in the state. It is not lost on anyone that this is where his story begins, in the literal shadow of prison walls.

His father was a chronic alcoholic who beat his children with whatever was nearby — belts, bricks, it didn't matter. Police were regular visitors to the Garrow farm in Mineville. By the time Robert was fifteen, authorities removed him from the home and sent him to a prison farm to work. A prison farm. As the intervention. For a fifteen-year-old boy. What it produced was a deeply isolated teenager with no therapeutic support, left alone with his own unraveling psychology in an institutional setting.

He eventually joined the Air Force. That ended in a court-martial for stealing from a superior officer. Back to New York, married a woman named Edith, had a son, found work as a mechanic in Syracuse. In 1961, he was convicted of first-degree rape of a sixteen-year-old girl and assault of her boyfriend. Ten to twenty years. Paroled in 1968.

He got a job at a baking company in Syracuse. Coworkers described him as hardworking and powerfully built, six foot two. But by the early 1970s, whatever containment had existed was gone. In May 1973, he abducted and molested two young girls from a Syracuse ice cream stand and held two Syracuse University students who were hitchhiking against their will. Both students survived. But now he had court dates approaching, active parole, and nowhere good for any of this to go.

The 1973 Adirondack Murder Spree: Alicia Hauck, Daniel Porter, Susan Petz, and Philip Domblewski

On July 11, 1973, the day before he was due in court, Garrow disappeared. On that same day, sixteen-year-old Alicia Hauck vanished on her way home from school. She had been hitchhiking. Garrow picked her up, drove her to a secluded area near the Syracuse University cemetery, and when she tried to run, he killed her with a hunting knife and buried her body behind a maintenance shack at Oakwood Cemetery. Then he drove north, toward the mountains, toward a wilderness he knew better than most people ever would.

Three days later, twenty-three-year-old Harvard student Daniel Porter and his twenty-year-old girlfriend Susan Petz were camping near Wevertown when Garrow found their campsite. He stabbed Porter to death. He took Petz captive, held her for several days, assaulted her repeatedly, then killed her and dropped her body into a mine shaft in Mineville, the same town where he had grown up. Porter's body was recovered six days later. Susan Petz would remain missing for months, her family not yet knowing she was already gone.

On July 29th, Garrow came upon four young campers near Wells, south of Speculator. Eighteen-year-old Philip Domblewski was there with his friends Nick Fiorello, David Freeman, and Carol Ann Malinowski. Garrow tied all four to separate trees, close enough to hear each other but not see each other, told them he had killed before and would do so again, then stabbed Domblewski while the other three listened. All three worked free of their bonds and ran. Garrow disappeared into the Adirondacks.

The Largest Manhunt in New York State History

His abandoned Volkswagen was found near the scene the next day, the license plate confirming the name law enforcement was now hunting across the entire region. What followed was the largest manhunt in New York State history. Hundreds of officers and state troopers pushed into the Adirondacks. Helicopters ran infrared sweeps at night. Campgrounds were evacuated and roads were blocked. And over loudspeakers mounted to those helicopters, authorities broadcast a recording on continuous loop — the voice of Garrow's wife Edith, playing on repeat over six million acres of forest: "Honey, this is Edith. Won't you please come out? Leave your rifle in the woods." That is a very specific 1973 approach to a manhunt.

Garrow stayed ahead of the search for twelve full days, breaking into hunting camps for food and moving parallel to roads to avoid checkpoints. In surrounding communities, the dread was something locals described for decades as never fully lifting. Residents kept loaded guns by their doors. The state issued a public advisory telling anyone planning an Adirondack trip to cancel, and anyone already there to leave. The summer tourist season simply stopped.

A priest from North Creek named Father Ashline had the misfortune of bearing a strong physical resemblance to Garrow and was tackled and handcuffed by state troopers while going about his daily life. A local man named Walt Cuniff was met with shotguns leveled over patrol car hoods because his vehicle resembled one connected to the case. Only a nearby officer who recognized him personally kept that from becoming something irreversible.

Garrow was cornered on August 9th after police staking out his sister's home in Witherbee followed his nephew to a thicket where Garrow was hiding. Conservation Officer Hilary LeBlanc fired, striking Garrow in the foot, arm, and back. He was taken alive. And here is where the story becomes something American law schools are still teaching fifty years later.

The Buried Bodies Case: Attorney-Client Privilege and the Ethics Crisis of 1973

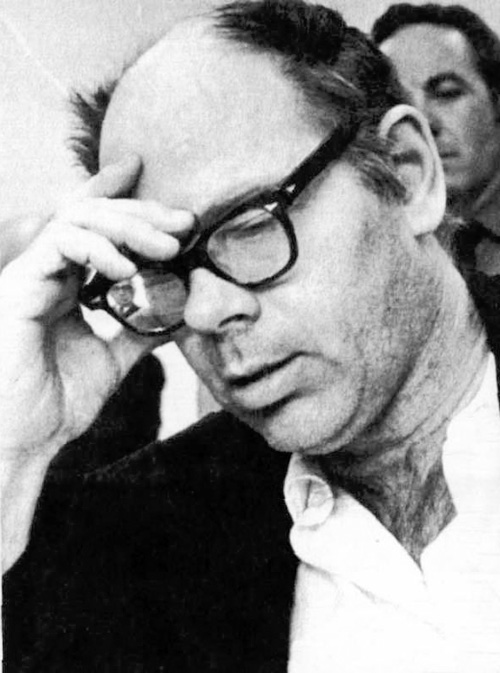

Frank Armani, a Syracuse attorney who had done minor prior legal work for Garrow, was appointed as defense counsel for the Domblewski murder. Armani brought in Francis Belge, a seasoned criminal defense attorney, to help build an insanity defense. During confidential client meetings, Garrow confessed to the murders of Alicia Hauck and Susan Petz and provided hand-drawn maps of where the bodies were located.

Armani and Belge went to those locations. They found Susan Petz in the Mineville mine shaft. They found Alicia Hauck's remains at Oakwood Cemetery. They photographed what they found. And then they told absolutely no one.

For five months, they held that silence while the families of both girls begged publicly for any information at all. Armani was a father himself. His daughter attended the same high school as Alicia Hauck's sisters. He knew Alicia's father personally. He described the experience later as playing God, holding his client's constitutional rights in one hand and the grief of a parent who simply wanted to know where his child was in the other. The attorneys offered to reveal the locations in exchange for Garrow being committed to a psychiatric facility. The district attorney refused. Trial proceeded.

The secret came out in court in June 1974 when Garrow testified about the other murders as part of his insanity defense, and a question Belge posed during testimony made it plain the defense team had known about the bodies for months. Both attorneys were publicly condemned. Their practices collapsed. Armani suffered a heart attack under sustained death threats. Belge was indicted for failing to report a death, though a judge ultimately dismissed the charges while acknowledging that Belge had honored his legal obligation at extraordinary personal cost.

Robert Garrow's Prison Escape, the Hit List, and His Death

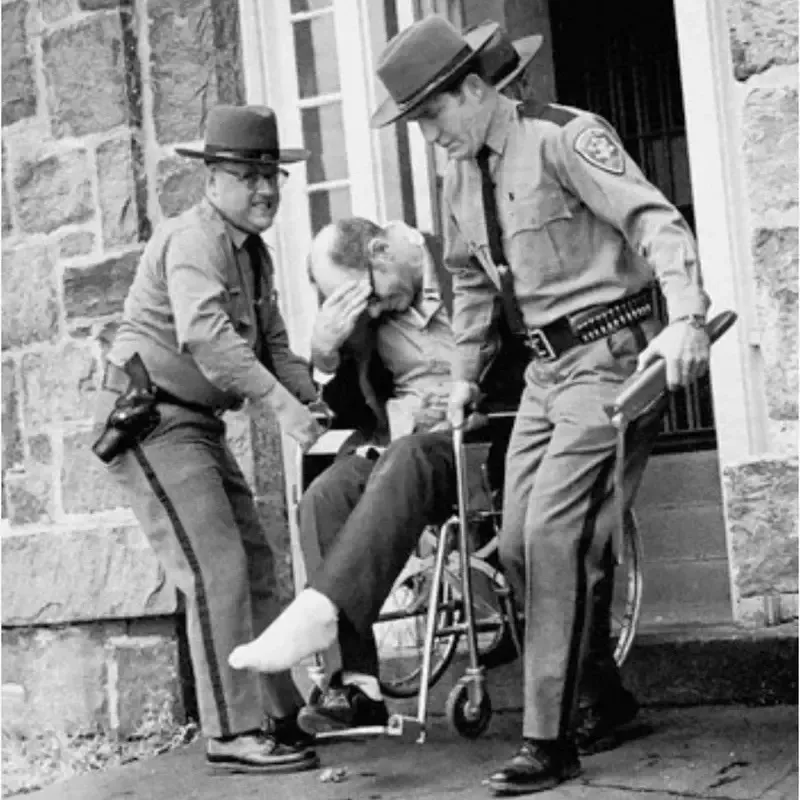

Garrow was convicted of second-degree murder and sentenced to twenty-five years to life. He was not finished. While incarcerated, he faked paralysis so convincingly over such a sustained period that medical staff transferred him to the medium-security Fishkill Correctional Facility, which housed elderly and disabled inmates. Lower security. Which was the entire point.

On September 8, 1978, his son Robert Jr. smuggled a .32 caliber pistol inside a bucket of fried chicken during a visit. Garrow rose from his wheelchair, scaled a fifteen-foot fence, and walked into the woods. When staff searched his cell, they found a hit list. Frank Armani's name was on it. Francis Belge's name was on it. The two men who had sacrificed their reputations and their health to uphold Robert Garrow's constitutional rights were the people he planned to find first.

Armani responded by helping police build a psychological profile of Garrow's likely movements, suggesting he would stay near the woods surrounding the prison. Three days after the escape, on September 11, 1978, correction officers spotted Garrow in a shallow depression he had scooped out by hand in the brush near the facility. When they moved in, he opened fire and wounded an officer. The response was overwhelming. Robert Garrow was forty-two years old.

The Legacy of the 26 Red Dots: How the Robert Garrow Case Changed American Law

A map recovered from his Volkswagen years earlier had twenty-six red dots on it. Four murders are officially attributed to him. The remaining dots have never been explained. The Buried Bodies Case is now standard curriculum in American law schools and directly influenced the ABA's Model Rule 1.6, which now gives attorneys limited circumstances under which they may break confidentiality to prevent death or serious bodily harm. Two attorneys did exactly what the law required of them and paid for it in ways the law never anticipated. And somewhere in the accounting of Robert Garrow's life, there are still dots on a map with no names attached to them.