Bible Belt Strangler: The 40-Year Hunt for a Killer Who Targeted Redheads

There's a stretch of Interstate 75 in Tennessee where, in January 1985, they found a young woman's body down an embankment. Bound. Strangled. Pregnant. Red hair. She'd stay nameless for 33 years. They called her Campbell County Jane Doe. Her name was Tina Farmer, and she was 21 years old. And the man who killed her? He might have killed a dozen more women just like her. Or maybe he didn't. That's the problem.

The Highway Killer Nobody Could Name: Unraveling the Redhead Murders

Between October 1978 and 1992, someone was killing women with red hair and leaving them along highways across the American South. That's 14 years. Maybe five victims. Maybe 14. The FBI opened a task force. Local cops coordinated across state lines, which back then was basically unheard of. For over 40 years, most of these women had no names. They were Jane Does. Numbers in a file.

When nobody knows who you are, nobody's looking for your killer either.

When the Bodies Started Appearing

The first victim showed up in 1978. Then another in 1983. By 1984 and 1985, bodies were appearing every few months. Tennessee, Arkansas, Kentucky, Mississippi, Pennsylvania, West Virginia. All found within a few dozen yards of major interstates. I-75. I-40. I-24. Women in their teens, twenties, thirties. All with reddish hair. Most strangled. Some beaten. A few left partially clothed or naked. One was stuffed inside a refrigerator and left on the side of the road.

The pattern was obvious. A mobile killer. Probably a trucker. Someone who spent his days on those long southern routes, picking up women who were hitchhiking or working the truck stops. Women who wouldn't be missed right away. Women whose families might not even know they were dead.

The media gave him a name: the Bible Belt Strangler. We give the killer a nickname. A brand. Meanwhile, the women stay anonymous.

The Victims the System Forgot

Let's talk about why these women stayed unidentified for so long. Bad forensic science played a role. Who they were played a bigger role.

Most of the Redhead Murder victims were transient. Hitchhikers. Sex workers. Women who'd been estranged from their families. Women who existed on the margins of society in a way that made them invisible. In the 1980s, if you were a woman working the streets or hitching rides on the interstate, the system wasn't set up to protect you. When you went missing, there wasn't a whole lot of urgency to find you.

Lisa Nichols was 28 when her body was found along I-40 near West Memphis, Arkansas, in September 1984. She was estranged from her family. She got identified pretty quickly through fingerprints in 1985. Tina Farmer was found in January 1985 near Jellico, Tennessee. Tina was 21. She was pregnant. She was bound and strangled and left down an embankment off I-75. She stayed nameless until 2018. Thirty-three years.

Why? Because nobody reported her missing. Because she'd been living on the road. Because she was the kind of person the system was built to overlook.

The One They Finally Connected

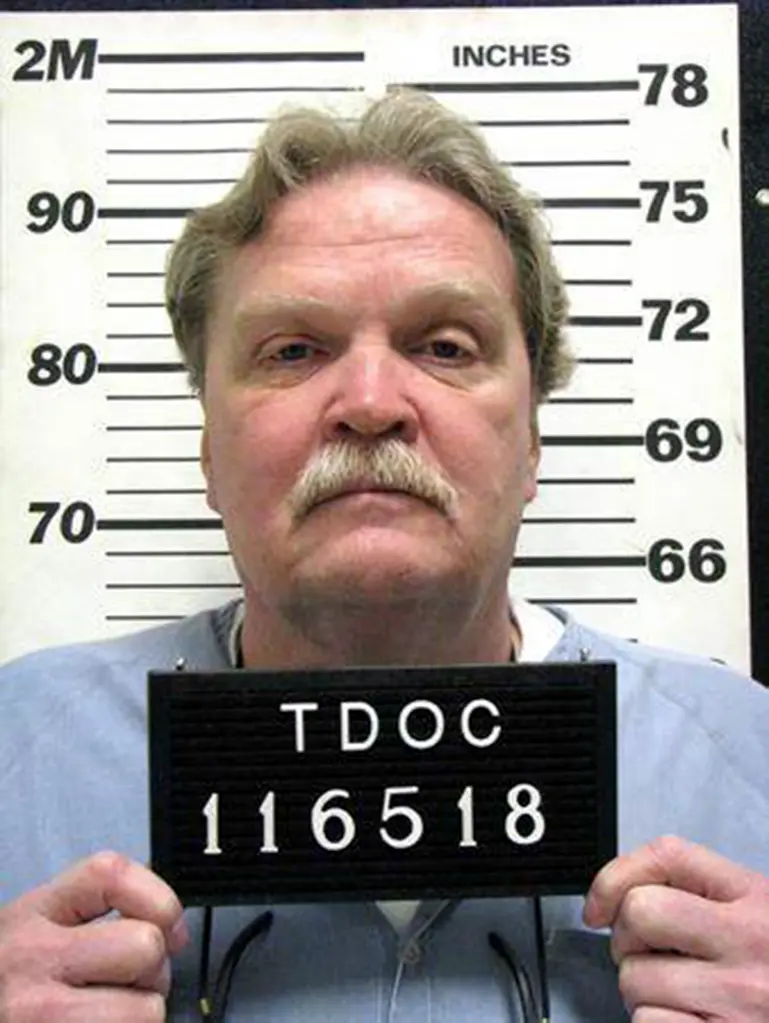

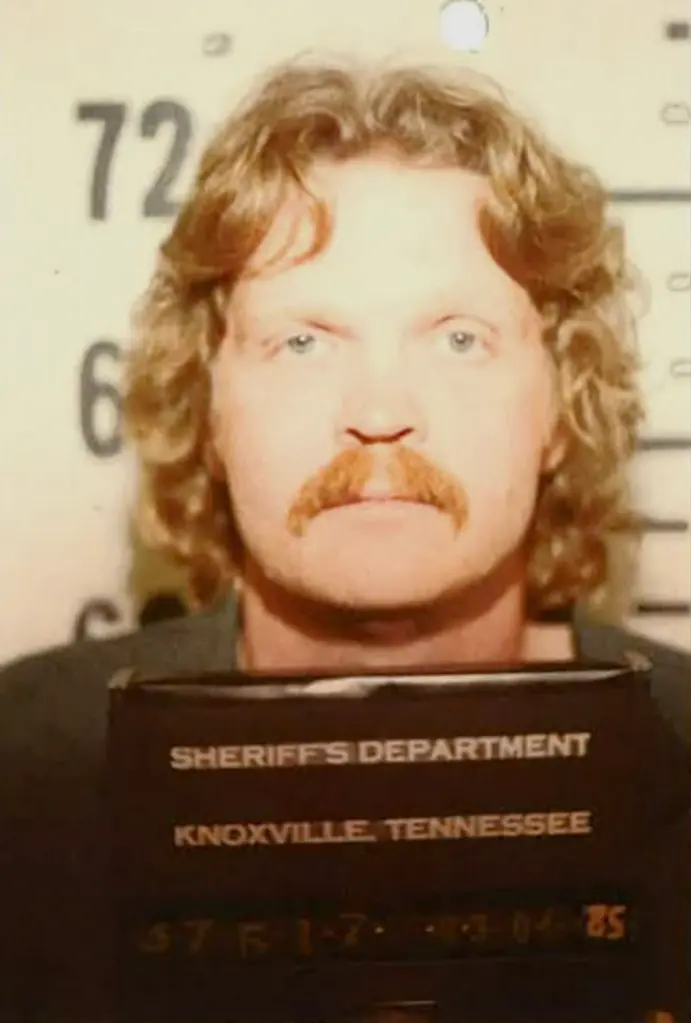

In 2019, investigators with the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation finally got a DNA match. The man who killed Tina Farmer was Jerry Leon Johns. A truck driver with a violent history. Exactly the profile everyone had suspected.

In March 1985, just two months after Tina's body was found, Johns kidnapped another woman. Her name was Linda Schacke, and she was a redhead. He bound her, strangled her with a piece of fabric ripped from her own T-shirt, and dumped her in a storm drain near I-40. Linda survived. She testified against him. Johns got convicted of aggravated kidnapping and assault in 1987 and went to prison. He died there in 2015, four years before the DNA linked him to Tina.

Linda's testimony is critical. She's the only person who lived through an encounter with Jerry Johns and can tell us exactly what he did. How he operated. How he picked his victims. Her account gives us the clearest picture we have of his method, and it matches what happened to Tina almost exactly.

Did Jerry Johns kill all of them? Or just Tina?

One Killer or Many?

Special Agent Brandon Elkins with the TBI has been clear about this. They've made a positive connection between Jerry Johns and Tina Farmer. They've made a positive connection between Johns and Linda Schacke. They haven't connected him to any of the other Redhead Murder victims. Espy Pilgrim, who was found in Kentucky in April 1985. Tracy Sue Walker, who was 15 and found in Jellico that same month. Michelle Inman, found along I-24 in Tennessee in March 1985.

The inconsistencies are the problem. Some of these women were strangled. Others were beaten to death. Some were found clothed. Others weren't. The dump sites were similar, the methods varied enough that investigators have to consider the possibility that multiple killers were working the same routes, targeting the same kind of woman.

The interstates in the South in the 1980s were crawling with truck drivers. Thousands of men moving through the same corridors every week. If you're a predator and you're looking for vulnerable women, truck stops and highway on-ramps are target-rich environments. More than one guy could have figured that out.

We don't know. Jerry Johns killed Tina Farmer. That's a fact. Whether he killed the others is still an open question.

The High School Kids Who Cracked the Profile

In 2018, before the TBI even announced the DNA link to Jerry Johns, a high school teacher in Elizabethton, Tennessee, named Alex Campbell started a sociology project with his students. The goal? Profile the Redhead Murders killer.

These kids were teenagers taking a sociology class. They had help from a former FBI agent, and they approached the case methodically. They studied the crime scenes. They looked at the highways. They paid attention to the terrain.

And they noticed something. Most of these bodies were found dozens of yards away from the road. Up or down steep embankments. Through thick brush. There were no drag marks. That meant the killer had to be strong enough to carry a body over rough ground.

So the students concluded: the killer was probably a large, physically strong male. Probably a truck driver, given the geographic spread of the dump sites. Someone who could move freely across state lines without raising suspicion.

Months later, the TBI announced they'd identified Jerry Johns. A truck driver with the physical strength to match. Exactly the profile the students had built.

The students even launched a podcast called Murder 101 to document their work. They may have actually helped identify Tina Farmer. They never got official credit for it. The TBI didn't acknowledge their work publicly.

How Forensic Genealogy Gave Them Their Names Back

For decades, the biggest obstacle in this case was identification. You can't solve a murder if you don't know who the victim is. In the 1980s, if a woman didn't have ID on her and nobody reported her missing, she stayed a Jane Doe.

Then forensic science caught up.

In the early 2000s, DNA technology advanced to the point where investigators could pull usable profiles from old evidence. By 2018, investigative genetic genealogy, or IGG, became a game changer. IGG takes DNA from a crime scene and uploads it to public genetic databases like GEDmatch. Then genealogists build family trees, working backward from distant relatives to identify the victim or the perpetrator.

That's how they identified Tina Farmer in 2018. Espy Pilgrim, the woman found in the refrigerator in Kentucky, was also identified in 2018 through a DNA match with her grown daughter. Tracy Sue Walker, who'd been a 15-year-old Jane Doe since 1985, was identified in 2022. Michelle Inman was identified in July 2023.

These identifications gave families answers after 30, 40 years of not knowing. Being Espy Pilgrim's daughter, finding out through a DNA test that your mother had been dead since 1985. That's the human cost of these cases. That's what gets lost in the headlines.

What We Still Don't Know

Tina Farmer's killer is dead. Jerry Johns died in prison in 2015. The others? Espy Pilgrim, Tracy Sue Walker, Michelle Inman, Lisa Nichols. We still don't know who killed them. We don't know if it was Johns and the DNA evidence hasn't caught up yet, or if there were other men out there doing the same thing.

There might still be victims we don't know about. The FBI task force estimated between five and 14 murders. That's a pretty big range. It suggests there are Jane Does out there who fit the pattern and were never officially connected to the case.

The Redhead Murders aren't fully solved. They're partially solved. One confirmed killer. Multiple victims. A lot of unanswered questions about who else might have been out there on those highways, hunting women nobody was protecting.

Jerry Leon Johns

Why This Story Matters

This case matters because it exposes how the system fails certain people. These women were poor, transient, living on the margins. They were killed and then erased. For decades, they didn't even have names.

It took 40 years and a brand-new technology to force us to remember them. The Redhead Murders are a reminder that all victims don't get the same attention. All cases don't get the same resources. Sometimes justice takes 40 years because nobody thought the victim was worth the effort.

Now we know their names. Tina Farmer. Espy Pilgrim. Tracy Sue Walker. Michelle Inman. Lisa Nichols. They were real people. They mattered. Their stories deserve to be told.