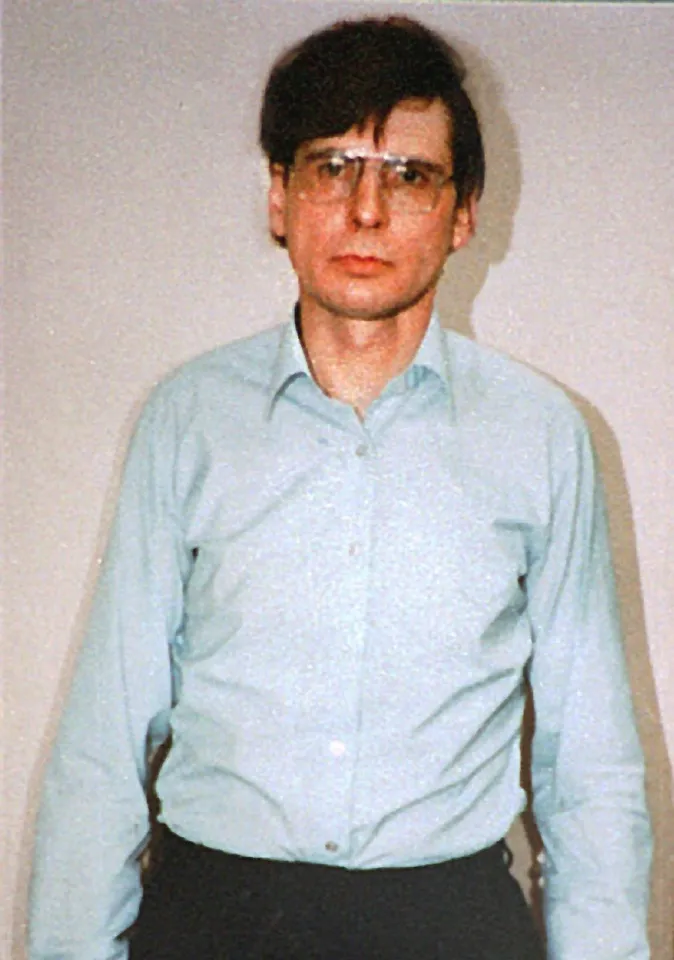

Burned and Flushed: The Dennis Nilsen Serial Killer Case

Between 1978 and 1983, Dennis Nilsen murdered at least twelve young men in North London. He kept their bodies as companions, burned them in his garden, and when that became impossible, tried flushing them down the toilet. Police ignored survivors who reported him. The case only broke when a plumber found human fingers blocking a drain. This is the story of the killer, the victims nobody looked for, and the system that failed them all.

The Discovery That Ended a Five-Year Killing Spree

So there's this moment in February 1983 when a plumber named Michael Cattran is standing outside an apartment building in North London, looking down into a drain that's completely blocked. He's been called because residents are complaining about the smell and the backed-up toilets. When he gets the drain cover off and shines his light down there, he sees what looks like flesh. Actual flesh. And four human fingers.

Dennis Nilsen, the tenant from the attic flat, comes out to see what's happening. Cattran shows him what he found. And Nilsen, completely calm, says it looks like someone's been flushing down their Kentucky Fried Chicken.

Kentucky Fried Chicken.

That's how Dennis Nilsen's five-year killing spree ended. Not because of brilliant detective work. Not because someone connected the dots. Because he tried to flush pieces of his victims down a toilet that couldn't handle what he was asking it to do.

Dennis Nilsen's Early Life and Path to Murder

Let's go back to the beginning.

Dennis Andrew Nilsen was born in November 1945 in Fraserburgh, Scotland. When he was six years old, his grandfather died. Nilsen was close to him, really close, and the death hit hard. What came next might have been worse. His family took him to view the body at the funeral. For a six-year-old kid, seeing someone he loved lying there dead created this twisted connection in his brain between affection and death, between love and loss and corpses.

Later in life, Nilsen would point to that moment as the thing that broke something inside him. Whether that's true or another convenient explanation, we'll never really know. There's some debate about whether Nilsen was being honest about his childhood or constructing a narrative that absolved him of responsibility.

From Army Butcher to Serial Killer

At sixteen, Nilsen joined the army. He worked in the Army Catering Corps as a cook and a butcher. He learned how to break down animal carcasses, how to cut through bone and tissue, how to portion things out efficiently. These were practical skills for military food service. They also turned out to be practical skills for something much darker.

After leaving the military in 1972, Nilsen tried joining the police. During his training, he developed this fascination with morgue visits and autopsied bodies. The people who knew him said he seemed drawn to death in a way that wasn't normal, even for someone training in law enforcement. He didn't last long in police work. Eventually, he ended up working a civil service job, helping unemployed people find work at a job center in Kentish Town. The kind of boring administrative position thousands of people do every day.

Underneath that ordinary exterior, Nilsen was struggling with something he couldn't resolve. He was gay, living in a time and place where that came with its own challenges. More than that, he desperately wanted companionship but couldn't handle the emotional complexity of an actual relationship. He wanted someone there, someone who wouldn't leave, someone who wouldn't reject him. Someone who wouldn't make demands or have their own needs.

His solution was murder.

Stephen Holmes: The First Victim of Dennis Nilsen

On December 30, 1978, Nilsen committed his first confirmed killing at his home on Melrose Avenue in North London. The victim was fourteen-year-old Stephen Holmes. The boy had been to a rock concert in Willesden and was trying to buy alcohol at the Cricklewood Arms pub when Nilsen met him. Nilsen brought him home, they drank, and the next morning when Holmes tried to leave, Nilsen strangled him with a necktie. Then he drowned him in a bucket of water in the kitchen.

Stephen Holmes. Fourteen years old. His family had no idea what happened to him for almost three decades. It wasn't until 2006 that police confirmed he was Nilsen's first victim.

The Ritual: How Dennis Nilsen Kept His Victims

After the murder, Nilsen did something that would become his signature. He bathed the body. Dressed it. Kept it in his flat for days, sometimes weeks. He would sit with it, talk to it, create this illusion of companionship. The body became what he wanted. Silent. Compliant. Unable to leave.

This is necrophilia, the attraction to corpses. For Nilsen, it wasn't only sexual. It was about control and connection and this deeply broken need for presence without the risk of emotional pain. Psychologists who later studied his case described it as a way of deadening anything that felt threatening or dangerous in his desires.

When he was finally done with a body, when it started to decay too much to maintain the illusion, he would dissect it in his bathtub. His butchering skills from the army came back. He treated it like any other task, breaking the body down into manageable pieces.

The Melrose Avenue Murders: Burning Bodies in Garden Bonfires

At Melrose Avenue, he had a garden. He would burn the remains in bonfires. To cover the smell of burning human flesh, he'd top each fire with an old car tire. The rubber would burn and create this thick, acrid smoke that masked what was really happening.

Between 1978 and late 1981, Nilsen killed somewhere between ten and twelve people at that address. Young men, mostly. Many of them were vulnerable in some way. Gay men at a time when being openly gay could be dangerous. Homeless kids. Runaways. Sex workers. People whose disappearances often went unreported or were treated as low priority by police.

Kenneth Ockenden was a twenty-three-year-old Canadian tourist visiting relatives in London. Nilsen met him in December 1979 and strangled him with headphone cords. Sixteen-year-old Martyn Duffey was homeless, lured back with promises of shelter and a meal in May 1980. Billy Sutherland was twenty-six, a father who'd come to London looking for work. He visited the job center where Nilsen worked and never made it home.

Police Failures: The Survivors Dennis Nilsen Nearly Killed

And that's a critical part of this story. Nilsen wasn't some criminal mastermind. He wasn't particularly careful. There were survivors who got away. Andrew Ho, a student from Hong Kong, escaped after Nilsen tried to strangle him during what Nilsen claimed was bondage play. Ho reported it to police in October 1979. Douglas Stewart overpowered Nilsen and escaped. Paul Nobbs woke up with bruises and a cut throat, confused about what happened. Carl Stotter nearly drowned in Nilsen's bathtub before somehow regaining consciousness days later.

These men reported attacks to the police. They described being strangled, losing consciousness, waking up confused and injured. The police didn't follow up aggressively. These were young men from marginalized communities. The systemic homophobia of the time meant their reports were dismissed or minimized.

Nilsen kept killing because the system gave him room to operate.

The Move to Cranley Gardens: A Fatal Mistake

By late 1981, the situation at Melrose Avenue was becoming unsustainable. He'd had to burn so many bodies that neighbors were starting to notice. The logistics were getting messy. So Nilsen moved to a new place, an attic flat at 23 Cranley Gardens in the Muswell Hill area of North London.

This move changed everything. The new flat didn't have a garden. No space for bonfires. Nilsen needed a new disposal method, and the one he chose was catastrophically stupid. He started cutting bodies into smaller and smaller pieces and flushing them down the toilet.

Human tissue doesn't break down in plumbing the way Nilsen seemed to think it would. Bones don't dissolve. Flesh clogs pipes. Between late 1981 and early 1983, he killed at least three more people at Cranley Gardens. John Howlett, a twenty-three-year-old guardsman. Graham Allen, twenty-seven. And finally, Stephen Sinclair, a twenty-year-old struggling with addiction who Nilsen met on Oxford Street on January 26, 1983.

With each murder, more remains went into the drains. The system was backing up.

How Dennis Nilsen Was Finally Caught

Residents started complaining about the smell and blocked toilets. Nilsen himself even wrote a complaint letter about the plumbing. That's when Michael Cattran got called in on February 8, 1983. When he found the fingers and flesh in the drain, he told his supervisor, Gary Wheeler. They came back the next morning to find that overnight, someone had cleared most of the remains from the drain. Only scraps of flesh and four bones remained.

They called the police.

Detective Chief Inspector Peter Jay showed up with colleagues and waited for Nilsen to come home from work. When Nilsen arrived at 5:15 PM, Jay asked him directly where the rest of the body was. Nilsen didn't hesitate. He invited them inside and immediately started confessing. He told Jay he'd killed fifteen to sixteen young men, that he'd picked them up at pubs, brought them home, and strangled them.

The confession came fast, almost like a relief. Five years of secret murders, of maintaining this double life, of disposing of body after body. When he finally got caught, Nilsen seemed almost eager to unload it all.

Inside the flat, police found the smell of decomposition overwhelming. Nilsen showed them to garbage bags in his wardrobe filled with human remains. Body parts in a tea chest. More remains under a drawer in the bathroom. He calmly directed them to everything, like he was giving a tour.

Police searched both residences. At Cranley Gardens, they found remains of three victims. At the old Melrose Avenue address, they found charred bone fragments in the garden, evidence of all those bonfires.

Dennis Nilsen Trial and Conviction

Nilsen went to trial on October 24, 1983, charged with six counts of murder and two counts of attempted murder. His defense argued diminished responsibility, claiming an abnormality of mind reduced his culpability. The diagnosis that seemed to fit was Schizoid Personality Disorder, a condition characterized by detachment from social relationships and emotional flatness. For Nilsen, that meant wanting companionship but being psychologically incapable of handling the emotional demands of an actual living person.

During the trial, prosecutors presented Nilsen's own writings. In one passage, he compared the murder process to a meal. The victim was the dirty platter after the feast. Disposing of the body was only washing up, a clinically ordinary task. That metaphor tells you everything about how he viewed his crimes. The murder was functional. It gave him access to what he wanted: the body, the silent companion. Everything after was cleanup.

The jury didn't buy it. On November 4, 1983, Nilsen was convicted and sentenced to life in prison with a recommendation of twenty-five years minimum. In 1994, that was upgraded to a whole life tariff.

Dennis Nilsen's Prison Life and Autobiography

In prison, Nilsen spent nearly two decades writing his autobiography, six thousand pages called "History of a Drowning Boy." The Home Office blocked its publication while he was alive. It was eventually published after his death, with a foreword warning readers not to take Nilsen's self-analysis at face value.

Dennis Nilsen died on May 12, 2018, at York Hospital. He was seventy-two. The cause was a pulmonary embolism and internal bleeding following surgery for an abdominal aortic aneurysm.

The Legacy of Dennis Nilsen: How Society Failed His Victims

The real legacy isn't only about one killer. It's about how society failed the victims. These were young men whose lives were already precarious. When they disappeared, nobody looked very hard. When survivors reported attacks, police didn't investigate thoroughly. The systemic homophobia created an environment where Nilsen could operate for five years. Twelve to fifteen victims. Multiple survivors who tried to report him. And it only stopped because of a plumbing failure.

The Nilsen case is a reminder that protecting society means protecting all of its members, especially the most vulnerable. When we decide some lives matter less than others, when we allow prejudice to determine which disappearances deserve investigation, we create spaces where predators can thrive.

Dennis Nilsen was a broken person who did monstrous things. The system that allowed him to continue for five years was broken too.