Thanksgiving Day 2012: How Byron Smith Executed Two Teen Burglars

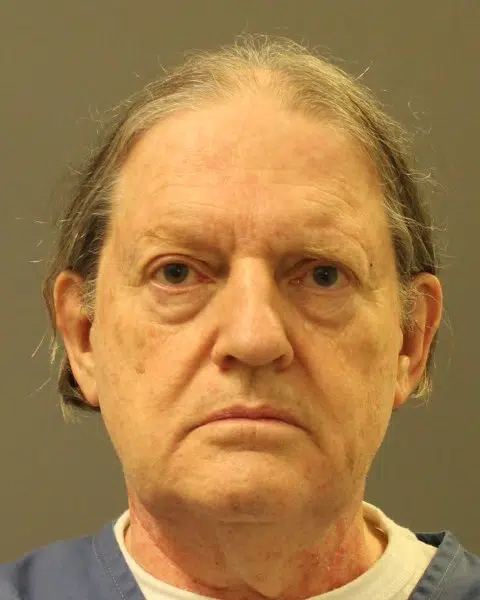

Sixty-four years old. Retired security engineer. Been burglarized so many times he's sleeping with a gun. Then on Thanksgiving 2012, two teenagers break into his basement. Byron Smith was ready. He'd moved his truck to make the house look empty. He was armed with two guns. And he turned on his audio recorder. What that recording captured would seal his fate for life.

When Your Castle Becomes Your Trap: The Byron Smith Murders

Byron Smith was sixty-four years old in 2012. Retired from the U.S. State Department where he'd worked as a security engineer setting up security at American embassies in places like Bangkok, Cairo, Beijing. That professional background becomes crucial because the prosecution would argue that someone with his expertise couldn't claim pure panic.

Smith had real reasons to be scared. In the months before Thanksgiving 2012, his house in Little Falls, Minnesota got hit repeatedly. Thieves took four thousand dollars in cash, his video camera, chainsaw, gold coins. But losing his father's POW watch devastated him. Irreplaceable sentimental value. Something deeply personal gets violated when a thief takes that from you.

Neighbors testified Smith looked terrified in those final weeks. Sleep deprived. Visibly upset. He started wearing a holstered gun around his own house. He began stashing water bottles and granola bars in his basement, preparing for an extended standoff. These actions become legally significant because they show preparation rather than spontaneous reaction.

The Teens With Inside Knowledge

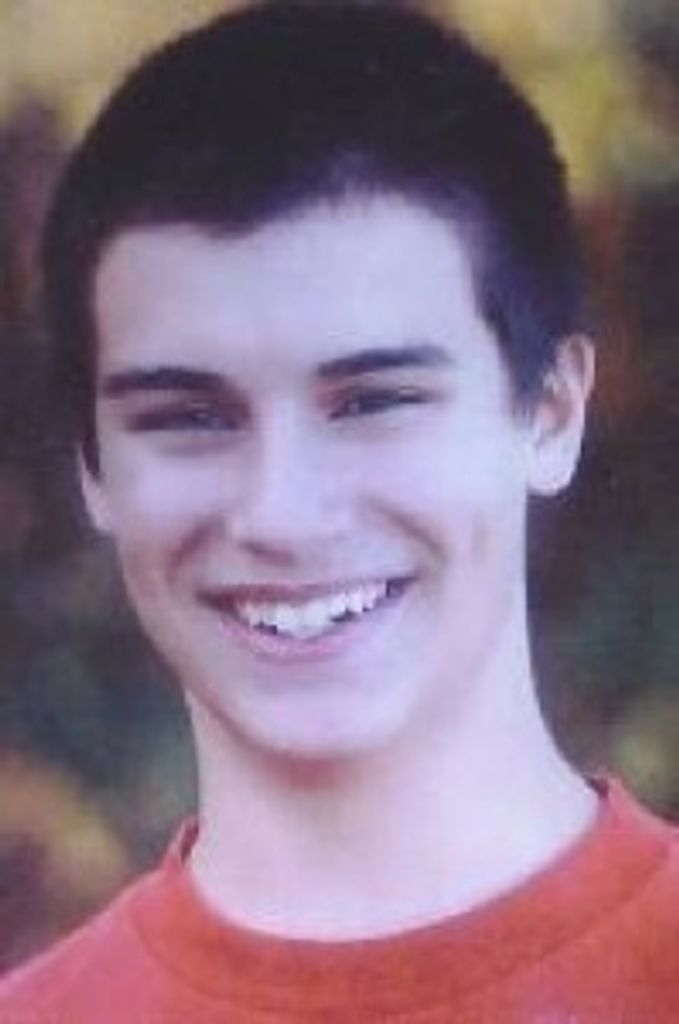

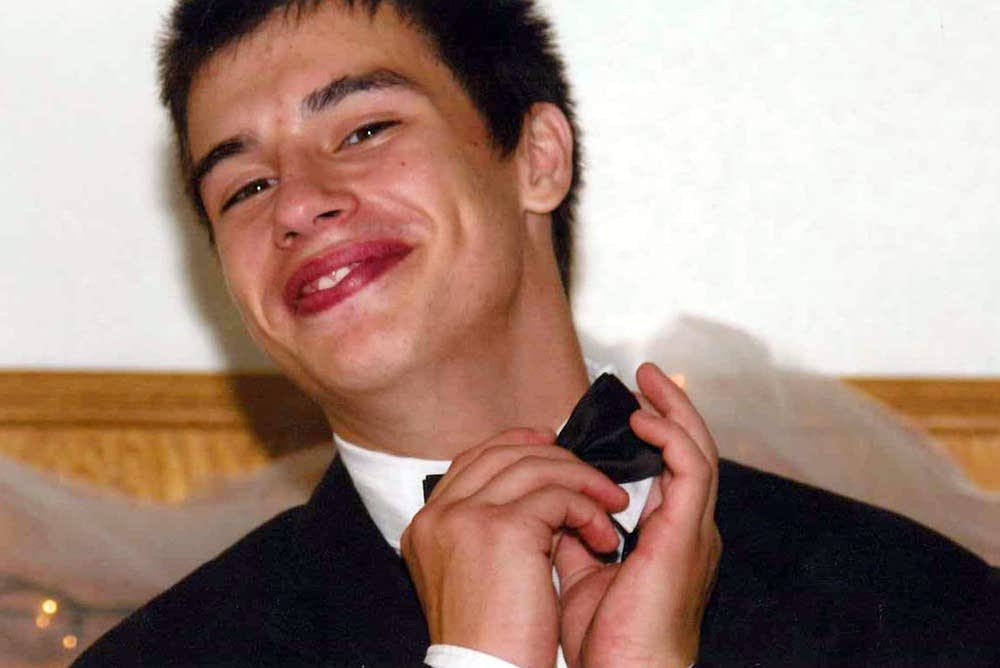

Nicholas Brady and Haile Kifer were cousins. Brady was seventeen, Kifer was eighteen. Police had linked Brady to at least two prior burglaries of Smith's property. Brady stole that cash, the video camera, the chainsaw.

Brady had an accomplice named Cody Kasper who'd actually done odd jobs for Smith. Yard work, cleaning up around the property. These teens had insider knowledge about what Smith owned and where things were kept. This was targeted activity.

The day before Thanksgiving, Brady and Kifer got connected to another burglary where they stole prescription medications. Investigators found those stolen pills in the car the teens were driving on Thanksgiving Day. Smith knew Brady had burglarized him. He felt targeted and believed law enforcement had done nothing to stop it.

Engineering an Ambush

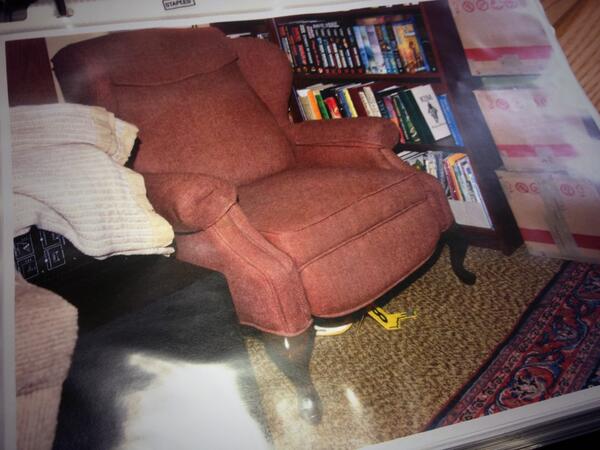

Thanksgiving morning, 2012. Smith drove his truck away and parked it at a neighbor's home. He wanted his house to look unoccupied. Then he went to his basement and positioned himself in a chair with a clear view of the stairway. He armed himself with two weapons: a Ruger Mini-14 rifle and a High Standard .22-caliber revolver.

Then Smith turned on his audio recording system. Six hours and twenty-five minutes of recording time. Maybe he thought this would prove his innocence. Instead, that audio became the prosecution's most powerful evidence.

Smith also unscrewed the lightbulbs in his basement. Intruders would be descending into darkness while he maintained tactical advantage. In legal terms, what Smith did is called lying in wait. Prosecutors argued he created conditions designed to lure intruders into a lethal trap.

The Killing of Nicholas Brady

Around 12:30 PM, Nick Brady broke in through a bedroom window. The audio captures breaking glass, then footsteps. Smith waited twelve minutes in silence. Then Brady started down the basement stairs.

Smith opened fire. Two shots hit Brady as he descended. Brady fell, groaning and wounded. Medical examiner testimony confirmed those initial shots were serious but wouldn't have immediately killed him.

Smith's rifle jammed. He switched to his .22-caliber revolver and fired a third shot. Close range through Brady's hand into his right temple. That head shot became the fatal wound.

The audio captures Smith saying "You're dead." Then the sound of Smith dragging Brady's body, wrapping him in a tarp, pulling him into a workshop. Heavy breathing. Smith reloading his weapon.

Then Smith waited. Ten full minutes pass on that recording.

Ten Minutes That Proved Murder

Haile Kifer entered the basement approximately ten minutes after her cousin. That time gap matters enormously. Ten minutes provides time to call 911, to secure the scene, to make different choices. Those ten minutes eliminate any argument that Smith acted in continuous panic.

The audio captures Kifer softly calling "Nick." She starts down the stairs. Smith fires. Kifer falls. His gun jams.

The recording captures him saying "Oh, sorry about that." Sarcastic. Mocking. Then Kifer screams "Oh my God!" clearly wounded and terrified.

Smith fires multiple more times. Six shots total. Between shots, he tells her "You're dying." He called her "bitch" multiple times. Smith dragged her body into that workshop and placed her on top of Brady's body.

Kifer was still breathing. Smith delivered one final shot under her chin. He would later describe this to police as "a good clean finishing shot." Those five words become the most damning evidence. That's execution language.

The audio later captured Smith's voice reflecting on what he'd done. He referred to both teenagers as "vermin." He described the killings as his civic duty. He said "I don't see them as human."

The Law's Limits

Minnesota law recognizes a form of the Castle Doctrine. Homeowners can use deadly force in their homes. You don't have to retreat. You can defend yourself if you reasonably believe you're facing death or great bodily harm.

The law requires your force be proportionate and necessary. Once the immediate threat stops, your legal right to continue shooting stops too.

Judge Douglas Anderson blocked most evidence about Brady and Kifer's criminal histories. The judge ruled that Smith didn't know who was breaking in when he started shooting. The trial focused on what Smith did after the initial threat was neutralized.

The prosecution had his own recording. The ten-minute wait between shootings. The taunting. The close-range head shots delivered to wounded teenagers no longer capable of harming anyone. The final finishing shots. All captured on audio Smith himself recorded.

The Aftermath

Smith didn't call 911 on Thanksgiving. He kept both bodies in his basement overnight. At one point on the audio, he practices what he'll say to lawyers. He whispers "In your left eye." Prosecutors noted Kifer was ultimately shot in her left eye, suggesting Smith had been rehearsing the killing.

Friday morning, Smith called a neighbor asking for a lawyer recommendation. That neighbor contacted the Morrison County Sheriff's Office.

When deputies arrived, Smith led them to the basement workshop where both bodies lay wrapped in tarps, stacked on top of each other. Brady had three gunshot wounds. Kifer had six.

Smith told investigators he'd "solved the break-ins in the neighborhood." He saw himself as solving a problem through violence because law enforcement had failed him.

Swift Conviction

Smith's defense attorney made a strategic decision. Smith would not testify at his murder trial. This probably aimed to prevent cross-examination about those recorded statements.

The prosecution played that audio recording. Fifteen minutes of condensed audio. The jury heard breaking glass, footsteps, gunshots, Brady groaning, Smith saying "You're dead," a body being dragged. Ten minutes of silence. Then Kifer's voice, more gunshots, her screams, Smith's mocking "Oh, sorry about that," more shots, Smith telling her "You're dying" and calling her "bitch." The final fatal gunshot.

The courtroom sat in silence except for family members sobbing.

The jury deliberated three hours. For a complex double murder case, three hours is remarkably fast. The audio recording did all the prosecution's work.

April 29, 2014. Guilty on two counts of first-degree premeditated murder. Guilty on two counts of second-degree murder. Smith was immediately sentenced to two concurrent life sentences without parole.

Smith's appeals went nowhere. He petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court in 2021. Denied. Currently, Smith remains incarcerated at Minnesota Correctional Facility Oak Park Heights.

In 2024, twelve years after the killings, Smith filed a civil defamation lawsuit against Jeremy Luberts, the lead investigator who'd written a book about the case. More than a decade into a life sentence, Smith is still fighting to control the narrative. Still convinced he was wronged.

Where the Line Gets Drawn

The Byron Smith case became a landmark. It defined exactly where Minnesota law draws the boundary between justified self-defense and criminal murder.

You can protect yourself when someone breaks in. You can use deadly force if you genuinely fear for your life. The Castle Doctrine means you don't have to retreat.

The moment the threat ends, your legal justification ends too. You don't get to execute wounded people. You don't get to deliver finishing shots to teenagers lying injured on your basement floor. You don't get to wait in ambush after engineering conditions to lure people into a kill zone.

Smith's security background worked against him. Someone with his training should have understood proportionate response. Should have recognized when a threat had been neutralized. Should have known to call law enforcement.

The jury heard all of it. The preparation. The lying in wait. The multiple weapons. The reloading between victims. The ten-minute gap proving separate intent. The taunting. The dehumanizing language. The execution-style head shots. And above all, Smith's own voice documenting his malice.

Nine total shots fired. Two dead teenagers who'd made terrible criminal choices. One audio recording that captured everything. A jury that needed three hours to unanimously agree this was premeditated murder.

The Castle Doctrine protects your right to defend your life in your home. It doesn't grant you the right to become judge, jury, and executioner. Byron Smith crossed that line on Thanksgiving 2012, and his own recording provided undeniable proof beyond any reasonable doubt.