The Truth About Ilse Koch and the Human Skin Lampshade Legend

She was called the Bitch of Buchenwald, the Witch, the Beast. Her name became synonymous with Nazi evil, her face plastered across newspapers worldwide. But here's what makes Ilse Koch's story so unsettling: the crime that made her famous might not have been hers at all. We're talking about human skin lampshades, systematic cruelty, and a legal mess that sparked international outrage. This is about how one woman became the perfect villain for a world desperate to make sense of the Holocaust, and how her actual, proven crimes got buried under sensational headlines. This is about truth, myth, and the monsters we need to believe in.

You can listen to this episode here.

How a Librarian Married Into Evil

So let's start with who Ilse Koch actually was before she became infamous, because that context matters.

In 1906, Margarete Ilse Köhler was born in Dresden, Germany. She wasn't born into Nazi royalty or raised in some dynasty of evil. She was ordinary. She worked as a librarian. That was her life.

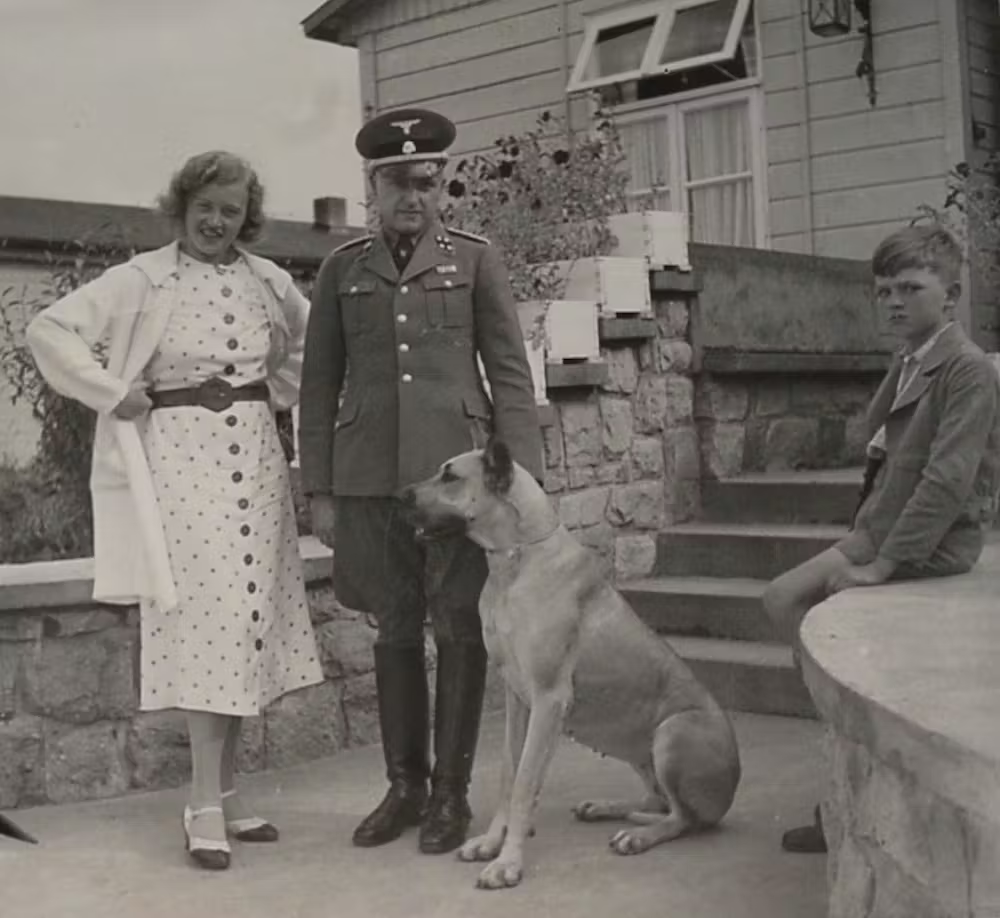

Then, on May 29, 1937, she married Karl-Otto Koch, an SS colonel who was already running the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. And just like that, her entire world changed. She went from stamping library books to living at the top of the Nazi concentration camp hierarchy.

When Karl-Otto got transferred to Buchenwald that same summer, Ilse went with him. And this is where things get dark fast, because even though she never held an official rank as a female guard, she had something arguably more powerful. She was the commandant's wife. That gave her this weird, unofficial authority that came with zero oversight.

The prisoners and guards started calling her the "Kommandeuse of Buchenwald." That title told you everything you needed to know about how power worked there. She could do basically whatever she wanted because she was sleeping with the man in charge.

Living Large While Prisoners Died

The lifestyle they maintained was absolutely obscene. We're talking lavish parties at their villa just outside the camp grounds, entertaining guests while thousands of people starved and died literally down the road. Ilse insisted that prisoners address her as "eine gnädige Frau," which translates to "a gracious lady."

Think about that for a second. A gracious lady. In a concentration camp.

She wanted to be seen as high society, as aristocracy. She was playing dress-up with absolute power over human lives, and she took that role seriously in the most horrifying way possible.

In 1940, she commissioned the construction of an indoor riding arena. A riding arena. This luxury project cost over 250,000 reichsmarks, which was about $100,000 in 1940 money. Multiple prisoners died building that facility so she could ride her horse indoors. That's documented fact.

The Cruelty That Was Proven

Ilse Koch earned every single one of her nicknames. The Witch of Buchenwald. The Beast. The Bitch of Buchenwald. These weren't media inventions. These came from survivors who lived through what she did.

Survivor testimony confirmed that she would ride her horse through the camp grounds dressed provocatively, deliberately taunting male prisoners. But here's the sick part. If any prisoner looked at her, even just a glance, he would be immediately beaten. Sometimes killed.

She created this impossible situation where she forced her presence on people and then punished them for the involuntary human reaction of seeing her. That's a special kind of sadism.

At her trials, witness Ludwig Tobias testified that Koch kicked out 13 of his teeth. Other witnesses confirmed she directly assaulted inmates on multiple occasions. She also reported prisoners to the SS for beatings, and at least one of those reports resulted in a prisoner's death. That's proven. That's in the legal record.

So when we talk about Ilse Koch, we're talking about someone who absolutely committed documented atrocities. That part isn't up for debate.

The Lampshade That Changed Everything

But the thing that made Ilse Koch internationally infamous wasn't the beatings or the riding arena or even the deaths she directly caused. It was the human skin lampshade.

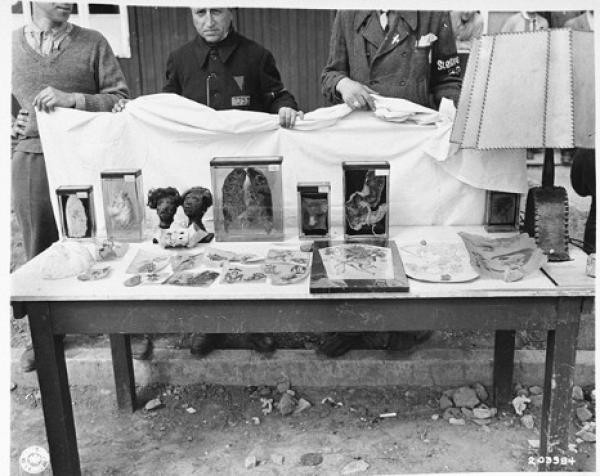

When American forces liberated Buchenwald in April 1945, they found artifacts made from human remains. Lampshades. Book covers. Pocket knife cases. General Eisenhower ordered photographers to document everything. They forced local German townspeople to tour the camp and see what had happened there.

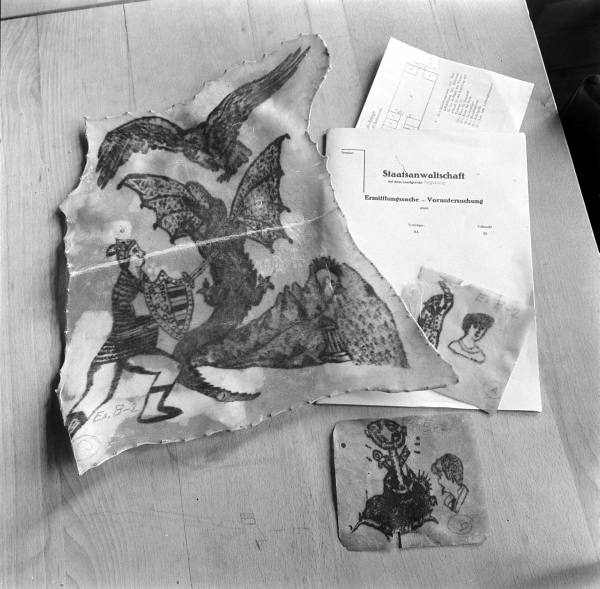

The images went global. The lampshade became this symbol of Nazi depravity that everyone could understand instantly. One lampshade in particular was reportedly made from a human foot and shinbone, and the shade itself showed tattoos and even nipples. A British soldier took a fragment of it, and decades later, scientific testing confirmed it was made of human skin.

These artifacts were real. That's historical fact. They were created starting in 1941 by the camp doctor, Dr. Hans Müller. Witnesses testified that Karl-Otto Koch and Dr. Müller would review tanned human skins and select ones with interesting tattoos for these projects.

But here's where the story gets legally complicated. The charge that defined Ilse Koch globally was that she personally selected tattooed prisoners and ordered their execution specifically to harvest their skin. That she was the driving force behind these grotesque objects.

When the Law Says One Thing and the Public Believes Another

Two separate courts, the 1947 American military tribunal and the 1950-1951 West German trial, both found that specific charge to be "without proof." Her defense successfully argued that while the artifacts existed and horrible things happened, there wasn't direct evidence linking her to ordering the killings for skin procurement.

Does that make sense? The lampshades were real. The murders were real. But proving she gave that specific order couldn't be done to the legal standard required for conviction on that charge.

The public didn't care about that distinction. At all. To everyone following the trials, the lampshade and Ilse Koch were inseparable. She became the face of that horror whether the legal record could prove it or not.

Three Trials and a Scandal

Ilse Koch actually faced three separate legal proceedings, and each one reveals something different about justice after the Holocaust.

In 1944, before the war even ended, the SS arrested both Koch and her husband. Not for murdering prisoners, mind you. For corruption. They were stealing from the SS, embezzling money, and killing witnesses who knew about their theft. The SS court found Karl-Otto guilty and executed him in April 1945, just days before Buchenwald was liberated. Ilse was acquitted due to lack of evidence and released after 16 months.

Then American forces found her. On June 30, 1945, she was recognized on the street in Ludwigsburg by a former prisoner and immediately arrested.

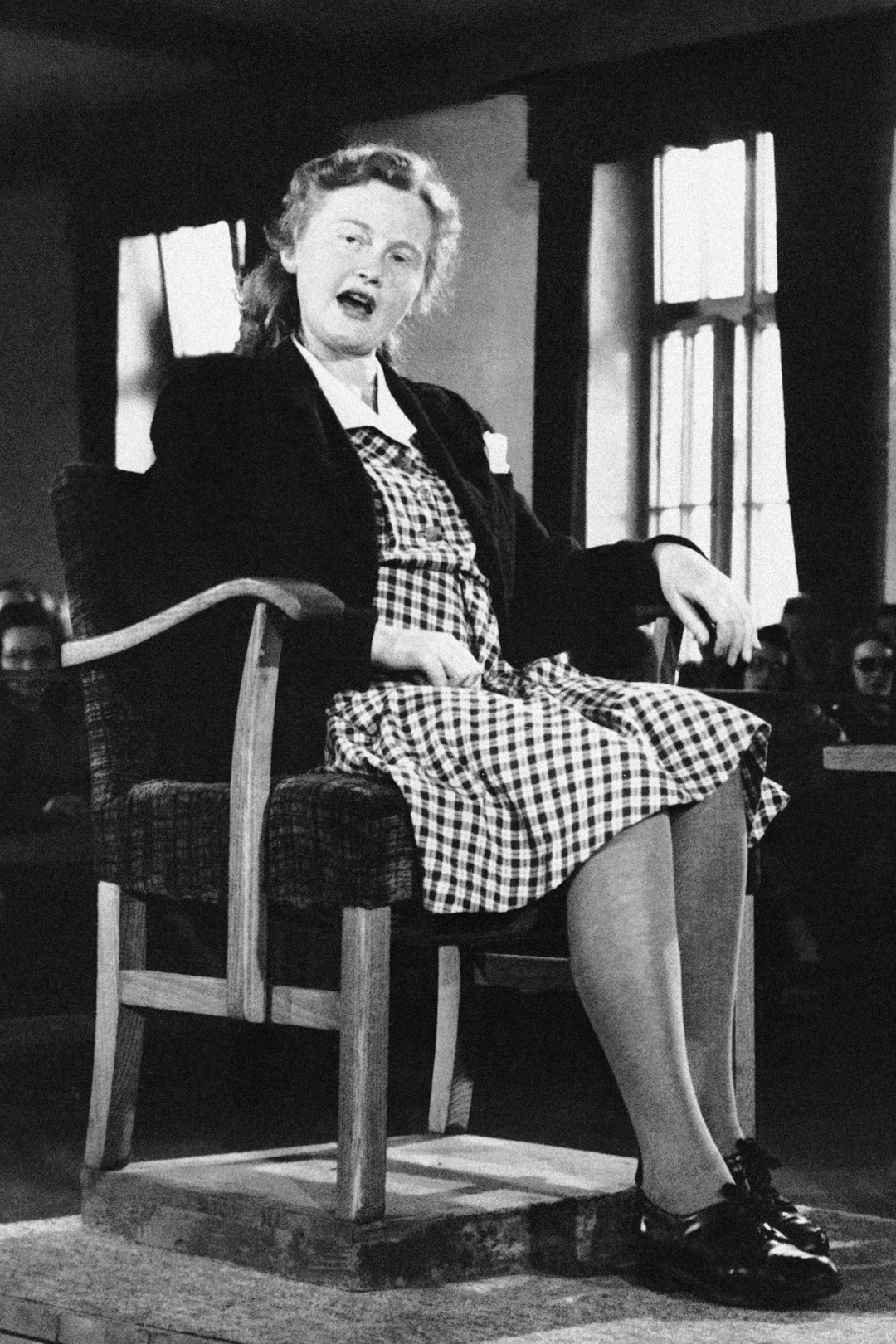

Her trial at Dachau in 1947 was massive international news. She was the only woman among 31 defendants. The prosecutor called her "no woman in the usual sense but a creature from some other tortured world." On August 14, 1947, she was convicted and sentenced to life in prison.

Twenty-two of her male co-defendants got death sentences. She didn't. And the reason why is genuinely wild. She was seven months pregnant with her fourth child. Nobody knew who the father was. Many people believed she got pregnant deliberately to avoid execution, using an old legal protection for pregnant women to save her own life.

The Clemency That Broke the World

In 1949, General Lucius Clay reviewed her case. He was required to follow strict legal standards, and when her lawyers argued there was insufficient proof for the most serious allegations, particularly the lampshade murders, he agreed. He commuted her sentence to four years, including time served.

She was released.

The global reaction was explosive. People lost their minds. The public saw this as a complete betrayal of justice, a moral failure of epic proportions. The outrage was so intense that it triggered a U.S. Senate investigation and required President Truman's personal intervention.

West German authorities immediately re-arrested her. This time they charged her with crimes against German citizens, which got around the jurisdictional limits of the American trial. During the proceedings in Augsburg, she put on quite a show, collapsing dramatically, screaming "I am guilty! I am a sinner!" and smashing furniture. Some doctors thought she was genuinely having a breakdown. Others thought she was faking it to delay the trial.

On January 15, 1951, she was convicted again and sentenced to life imprisonment. This time it stuck. She appealed to the International Human Rights Commission. Rejected in 1952. She petitioned for pardon multiple times. Denied every single time.

The Perfect Scapegoat

Ilse Koch spent 16 years in Aichach women's prison in West Germany. According to reports, she became increasingly paranoid and delusional, convinced that camp survivors would eventually come for her. On September 1, 1967, at age 60, she hanged herself with a bed sheet. Her suicide note to her son said, "There is no other way. Death for me is a release."

Here's what's so important to understand about her legacy. Ilse Koch absolutely committed horrific crimes. The beatings, the exploitation, the deaths caused by her abuse of power are all documented and proven beyond doubt.

But her transformation into the ultimate symbol of female Nazi evil served a purpose for post-war Germany. As the only woman among the Buchenwald defendants, her trials became these intense spectacles. Her conduct, including rumors of affairs and sexual humiliation of prisoners, was sensationalized through this lens that treated female violence as somehow more unnatural than male violence.

Scholar Tomaz Jardim argues that Koch became a national scapegoat. By focusing obsessively on her, on the perverse and partially unproven crimes like the lampshades, post-war German society could avoid confronting the harder truth. That millions of ordinary Germans participated in or enabled Nazi atrocities through boring bureaucratic complicity. Ilse Koch was spectacular evil. She was a monster. And that meant everyone else could distance themselves from the systematic nature of the Holocaust.

She became the exception that proved the rule, when really, she should have been a reminder of how normal people can do unthinkable things when given power and permission.

The human skin artifacts were real. Her cruelty was real. Her crimes were real. But the legend of Ilse Koch, the Bitch of Buchenwald who ordered prisoners killed for lampshade material, that became bigger than the legal truth. And maybe we needed that legend. Maybe post-war society needed a female face of evil that was so grotesque, so beyond normal comprehension, that it could carry the weight of collective guilt.

But that doesn't change what actually happened. And it doesn't change what we can prove. Ilse Koch remains one of the most hated figures of the Nazi era, caught forever between the monster she was and the myth she became.