Gulf War Ghosts: The Jeffrey Hutchinson Death Row Case

"I shot my family." Those four words changed everything for Jeffrey Hutchinson, a decorated Gulf War veteran whose mind had become another casualty of war. But what happened next would expose every crack in our justice system.

The Unheard Veteran: When Military Trauma Meets Family Tragedy

A Hero Returns Home Broken

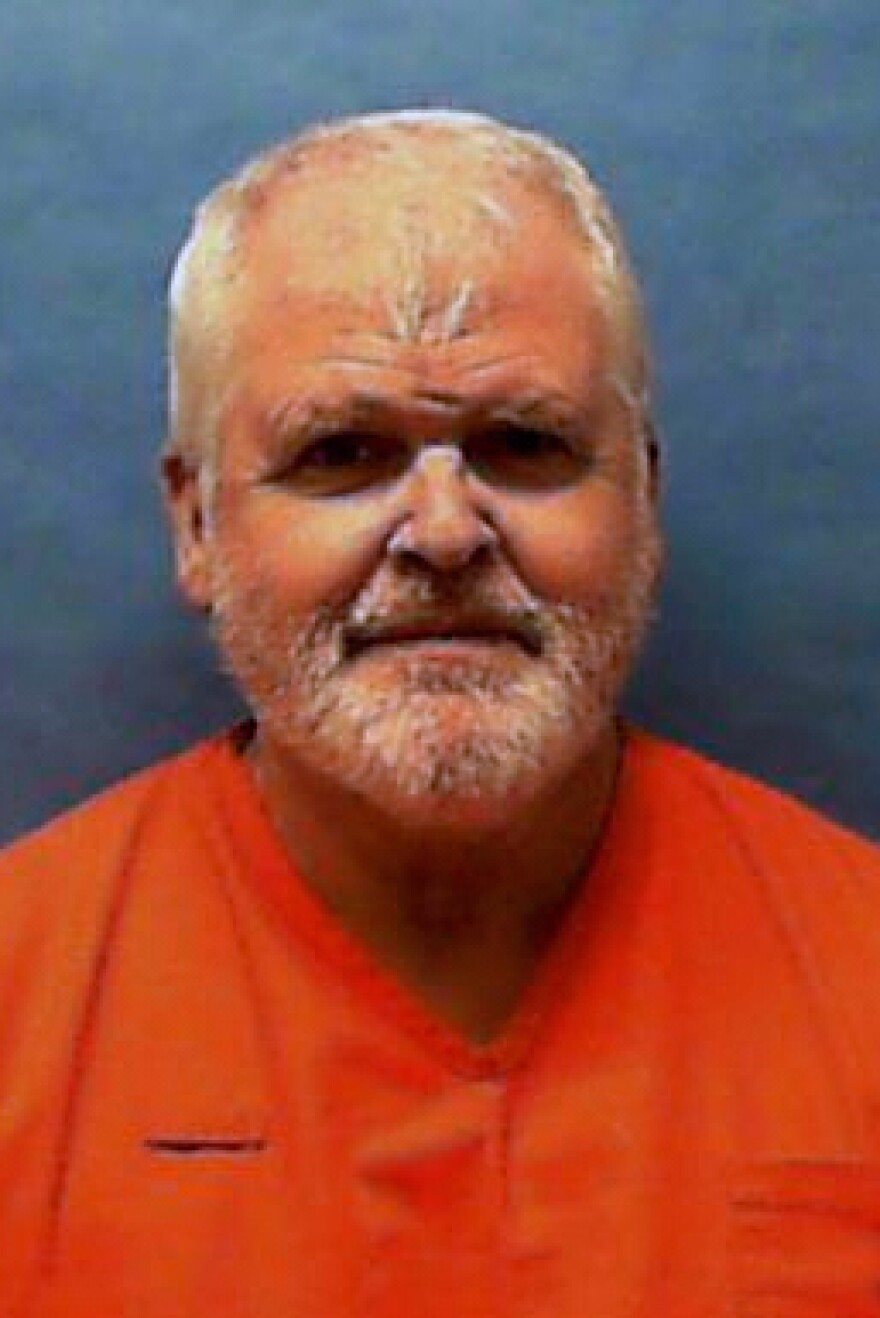

Jeffrey Hutchinson was supposed to be one of the good guys. Born in Alaska on November 6, 1962, he grew up in Kettle Falls, Washington, where by all accounts he was a regular kid dealing with ADHD. After high school, he worked as a mechanic and security guard, the kind of steady jobs that build communities. Then he made a decision that would define the rest of his life: he joined the U.S. Army.

Hutchinson became a paratrooper, earned his way into the Rangers, and when Operation Desert Storm kicked off, he answered the call. He served his country in the Gulf War, that quick but brutal conflict that sent thousands of young Americans into a desert filled with chemical weapons and burning oil fields.

But here's what nobody talks about enough: coming home from war doesn't always mean the war is over. When Hutchinson returned to the United States, he carried something invisible with him. A California psychiatrist would later diagnose him with Gulf War Illness, a condition that wreaks havoc on everything from sleep patterns to memory to basic cognitive function. The same doctor identified something called "neuro dysimmunity" and warned it could trigger "unconscious fits of rage."

This is where the story gets complicated, because we're dealing with a man whose brain was literally damaged by his service to his country, but the legal system he would eventually face had no real framework for understanding what that meant.

The Life That Came Before the Storm

After his discharge, Hutchinson tried to build a normal life. He moved to Spokane, Washington, where he met Renee Flaherty, a 32-year-old mother of three who was separated from her husband. By 1998, they'd moved together to Crestview, Florida, along with Renee's children: nine-year-old Geoffrey, seven-year-old Amanda, and four-year-old Logan.

People who knew them during this period described Hutchinson as a good partner and father figure. He treated those kids like they were his own, and neighbors saw what looked like a functional family unit. But underneath that surface, something was brewing that nobody fully understood at the time.

Gulf War Illness isn't like a broken leg you can see and treat. It's a constellation of symptoms that can include chronic pain, insomnia, memory problems, and yes, sudden bursts of uncontrollable anger. Veterans were coming home with these symptoms, and the medical establishment was still trying to figure out what the hell was happening to these people.

Hutchinson was living with diagnosed ADHD, Gulf War Illness, and the invisible wounds of combat trauma. He was trying to be a partner and father while his brain chemistry was fundamentally altered by his military service. That's the context for what happened next.

The Night Everything Shattered

September 11, 1998 started like a lot of domestic disputes do: with an argument between partners. Hutchinson and Renee got into it about something, and he responded by packing some clothes and guns into his truck and heading to a local bar. This wasn't unusual behavior for someone dealing with combat trauma. When everything feels overwhelming, sometimes you need to remove yourself from the situation.

While he was drinking, Renee called a friend in Washington. She thought Hutchinson had left for good this time, and honestly, maybe part of her was relieved. Living with someone struggling with untreated military trauma couldn't have been easy.

But around forty minutes after Hutchinson left the bar, someone placed a 911 call from the house that would haunt everyone involved for the next 27 years. The voice on that call said five words that changed everything: "I just shot my family."

Then, in what can only be described as a bizarre turn, the same caller started talking about masked intruders, claiming some guys from Quantico were at the house and they were responsible for the shootings. It was like listening to two completely different people on the same call.

When deputies arrived ten minutes later, they found Hutchinson on the garage floor, still connected to 911. His shotgun was on the kitchen counter. And inside that house was a scene that nobody should ever have to witness.

The Horror Inside

Renee and her two youngest children, Logan and Amanda, were found in the master bedroom, each killed with a single shotgun blast to the head. But it was what happened to nine-year-old Geoffrey that would become the legal lynch pin for Hutchinson's death sentence.

Geoffrey had tried to defend himself. The forensic evidence showed he'd been shot first in the chest, with the blast also hitting his arm as he tried to block it. But he didn't die immediately. Instead, he stumbled into the living room, fell to the floor, and was still conscious when Hutchinson reloaded that pump-action shotgun and fired a second shot into his head.

This sequence of events wasn't heat of passion. It was methodical, deliberate, and it would later be classified as "heinous, atrocious, and cruel" by the court. The forensic evidence was overwhelming: gunshot residue on Hutchinson's hands, Geoffrey's tissue on his clothing, and no injuries consistent with fighting off intruders.

But here's what makes this case so complex: the same man who could commit such methodical violence was also genuinely suffering from documented brain damage and trauma-related disorders. Those two realities can coexist, and that's what makes this story so difficult to process.

When the System Fails Its Own

Hutchinson's trial in 2001 should have been where his military trauma got a full hearing. His defense team presented evidence of his Gulf War Syndrome, his ADHD diagnosis, his military service record, and expert testimony about how chemical weapons exposure can alter brain function and behavior.

The prosecution had their overwhelming physical evidence, including that damning 911 call where two of Hutchinson's friends identified his voice saying he'd shot his family. They had forensics, they had timeline, they had everything they needed for a conviction.

But the sentencing phase is where things got interesting in a really dark way. Judge G. Robert Barton made a decision that reveals how the legal system tried to balance competing truths: he sentenced Hutchinson to life without parole for killing Renee, but death for murdering the three children.

The judge acknowledged Hutchinson's clean record and military service as mitigating factors for Renee's murder. But when it came to those kids, especially Geoffrey's brutal second shooting, the court decided that no amount of military trauma could excuse that level of cruelty to children.

The Procedural Nightmare That Silenced Everything

Here's where this case becomes a perfect example of how legal technicalities can completely override justice. Under federal law, death row inmates get one year after their state appeals are finalized to file in federal court. But calculating that deadline is incredibly complex, and Hutchinson's attorneys screwed it up.

They filed his federal habeas appeal three weeks late, thinking they had more time. This wasn't some lazy mistake. Hutchinson himself saw the danger coming. A week before the actual deadline, he told his lawyers point-blank to either file immediately or he'd fire them and do it himself. They promised they would file, but they didn't.

That procedural error meant no federal court ever reviewed the substance of his claims about military trauma and mental illness. The most important part of his defense was legally silenced because of a calendar mistake made by the very people supposed to save his life.

The legal doctrine that destroyed him is called "agency," which holds clients responsible for their lawyers' actions. But think about how absurd that is in this context: a brain-damaged veteran on death row is supposed to somehow monitor and control attorneys who specialize in complex federal deadline calculations?

The Final Battle Over His Mind

In his last weeks, Hutchinson's case came down to one final question: was he sane enough to execute? His legal team brought in psychiatrist Dr. Bhusan Agharkar, who diagnosed him with Delusional Disorder. For decades, Hutchinson had maintained that the murders were part of a government conspiracy to silence him, and his execution was the state's final move in that conspiracy.

The defense argued that while Hutchinson understood he was going to be executed, his delusion prevented him from rationally understanding why the state was doing it, which is the legal standard for competency.

But the state brought their own experts who painted Hutchinson as a manipulative liar whose conspiracy theories were contrived defense tactics, not genuine mental illness. Dr. Wade Myers testified he found "no evidence" of a fixed delusion at all.

The court sided with the state's experts, finding their opinions "credible and compelling." On May 1, 2025, Jeffrey Hutchinson was executed by lethal injection at Florida State Prison. He was pronounced dead at 8:15 p.m., becoming the fourth person executed in Florida that year.

The Questions That Died With Him

What makes Jeffrey Hutchinson's case so haunting isn't whether he was guilty. The evidence for that was overwhelming. It's that our system never truly grappled with what military trauma means in the context of criminal justice.

We send people to war, they come back with invisible wounds, and when those wounds contribute to unthinkable violence, we execute them without ever really examining our role in creating those wounds. 129 military veterans wrote to Governor DeSantis calling Hutchinson's mind "a casualty, like any limb lost in combat." Florida's Catholic bishops pleaded for mercy, acknowledging the victims' tragic deaths while arguing that life imprisonment served justice better than execution.

None of it mattered. The procedural error that kept federal courts from reviewing his military trauma claims meant the most important questions about his case were never answered. We'll never know if a full federal review of his Gulf War Illness and brain damage might have changed anything.

What we do know is that Jeffrey Hutchinson was both a decorated veteran who served his country and a man who committed horrific acts of violence against innocent children. Both of those things can be true simultaneously, and our justice system struggled to hold that complexity.

His execution ended not with resolution, but with the same contradictions that defined his entire case: overwhelming evidence of guilt alongside legitimate questions about whether a traumatized veteran's broken mind deserved death or treatment. Those questions died with him on May 1st, leaving us to wonder if justice was truly served or if we simply chose the easier path of permanent silence.