The Mob That Burned History: What Happened in Georgia

The Boiling Point in Brooks County

May 1918. Southern Georgia. Things weren’t exactly peaceful, but they were holding—barely. Tensions simmered just beneath the surface, like a pot someone forgot they left on the stove. And then someone turned the heat all the way up.

Enter Hampton Smith. Mid-twenties, wealthy, white, and unfortunately in charge of a lot more than just his own bad decisions. He ran a place called the Old Joyce Plantation near Morven in Brooks County. The guy had money, but when it came to character? That account was overdrawn.

Hampton needed labor to keep his fields productive and his profits steady. What he didn’t need, apparently, was any level of decency or humanity in how he got it.

Labor by Force: How Convict Leasing Fueled a Plantation’s Profits

Hampton Smith wasn’t just disliked—he was infamous. Known for beating his workers and squeezing every ounce of labor out of them, the man turned his plantation into a sweat-soaked nightmare. It wasn’t exactly a recruitment dream, and shocker: people didn’t line up for the job.

So Hampton did what many white plantation owners in the South were doing after the abolition of slavery—he went to jail. Not as an inmate, but as a shopper. Local Black residents were regularly arrested for things like “vagrancy” or, in this case, playing dice. Petty offenses or failure to pay inflated fines landed people in jail. And once they were inside, their bail could be paid by anyone—including men like Hampton—who’d then “lease” them for labor.

Convict leasing, they called it. A system that had all the hallmarks of slavery, just with slightly more paperwork. And in 1918 Georgia, it was thriving.

That’s how Sidney Johnson entered the picture. Young, Black, and physically strong, he caught Hampton’s eye like a Craigslist ad for a used truck that still runs. Thirty dollars to the county got Sidney out of jail and straight onto the Old Joyce Plantation.

Hampton didn’t exactly see Sidney as a person—he saw him as a return on investment. Sidney would eat when told, work until told to stop, and sleep only when there was nothing left to squeeze out of him. That was the plan.

But Sidney Johnson wasn’t built to be anybody’s property. And Hampton Smith? He was about to learn that the hard way.

The Breaking Point: Sidney Johnson Fights Back

Sidney Johnson may have been trapped in a system that treated him like property, but he never saw himself that way. He was a convict, yes. But a slave? No. Not in his mind. And that refusal to surrender his dignity? That made him dangerous.

He didn’t just take Hampton Smith’s cruelty on the chin. Sidney talked back. He challenged. He held onto what little agency he had, even when it earned him beatings. He had a sharp mind and a sharper mouth, and both of those things put a target on his back.

Still, he kept going. Until one day, he couldn’t.

Sidney got sick. Too sick to work. He said so. Hampton didn’t care. He beat him anyway. That moment broke something.

Sidney grabbed a gun from the property and made his way to the plantation house. Through a window, he saw Hampton and his wife. He pulled the trigger. Hampton’s wife was wounded but managed to get away. Hampton didn’t. He died instantly. Just like that, the man who had spent his life brutalizing others was gone.

Sidney fled, but what he left behind was more than a body. To the white community of Brooks County, this wasn’t just a killing. It was an uprising. An offense against the natural order they believed in.

They weren’t going to let that go.

A mob started forming. Angry. Armed. Looking for revenge. And they didn’t care if they had the right man. They just wanted blood.

Mob Justice and a Widening Target

After Hampton Smith’s death, anyone Black and anywhere nearby suddenly looked like a suspect. Didn’t matter if they had a connection to the crime or not. If your name was whispered in the wrong place, or if you’d ever had a run-in with Hampton, you were fair game.

And a lot of people had.

Two men, Will Head and Will Thompson, were taken by the mob and lynched. When it was over, their bodies had been riddled with bullets. Not once or twice. Over 700 times.

Then came Chime Riley. He didn’t work for Hampton. Had no known ties to the plantation. But that didn’t stop anyone. He was lynched too. His hands and legs were tied with turpentine cups before his body was thrown into the Little River.

The list kept growing.

But one name kept coming up near the top: Hayes Turner.

Hayes had worked under Hampton and had the scars to prove it. The two had history, and not the good kind. Hayes had taken a lot of abuse from Hampton until one day he stopped taking it. He pushed back. He threatened him.

That’s when Hampton made it personal.

To make an example of Hayes, Hampton grabbed his wife, Mary Turner, and beat her in front of him. Mary was eight months pregnant at the time.

People heard about what happened. But what they really latched onto was this: Hayes had motive. Strong motive. So he was arrested and hauled off for questioning.

Not to figure out what happened. Just to check a box.

The Mob Comes for Hayes Turner

Hayes Turner never made it to trial. While being transferred between jails, the mob got their chance. They ambushed the transport, ripped Hayes from custody, and lynched him. His body was left hanging from a tree for two full days. It wasn’t justice. It wasn’t law. It was rage, on display.

Back home, his wife Mary had no idea. She was caring for their two young children and preparing for the birth of a third. She found out the way a lot of people found out terrible things back then—through the newspaper.

And what she did next took courage most people couldn’t even fake.

Mary Turner Refuses to Stay Silent

Mary spoke up. Loudly. She called out the mob for killing her husband and said, publicly, that they should be arrested for it. In 1918 Georgia, that kind of statement from a pregnant Black woman was seen not just as bold—but as dangerous.

The mob turned its attention to her.

Mary tried to run, but they caught her before she could make it out of town. They dragged her outside the city limits. Then they tied her to a tree, upside down. They poured gasoline on her clothes and burned them off her body. And then, while she was still alive, they sliced open her stomach with a butcher’s knife.

Her unborn baby fell to the ground and let out two cries before someone in the mob stomped its skull with the heel of their boot.

Then they turned their guns on Mary. Hundreds of bullets. They didn’t just kill her... they tried to erase her.

The Lynchings Spiral Out of Control

The murder of Mary Turner and her child pushed the violence into something even darker. People started calling it what it was—the Lynching Rampage. And it wasn’t over.

Sidney Johnson, the man whose act of defiance had kicked all of this off, had escaped Brooks County and made it to neighboring Lowndes County. He stayed hidden for a while, but hunger will out you faster than anything else. Desperate, he asked another Black man for food.

That man went to the police.

Knowing Sidney was armed and had already killed a white plantation owner, law enforcement didn’t come lightly. A full armed unit surrounded the house where Sidney had holed up. A shootout erupted. Sidney managed to wound three officers, but he was fatally shot in the process. When they entered the house, he was already gone.

But the mob wasn’t done with him yet.

Even in Death, No Peace

Word spread fast. A crowd gathered outside the house, angry they’d been denied a lynching. So they took what was left of Sidney’s body, mutilated it, tied it to the back of a car, and dragged it through town.

They brought him back to the Old Joyce Place—right where this entire story started—and hung his body from a tree. Then they set it on fire.

Even after Sidney’s death, two more men were killed by mobs or courts trying to “finish the job.” When the rampage finally burned itself out, 13 people had been murdered. Mary Turner and her baby among them.

A Town Held Hostage by Fear

As the violence spiraled, over 500 Black residents tried to flee Brooks County. But even that wasn’t allowed. White residents made it clear—anyone who tried to leave could end up dead too.

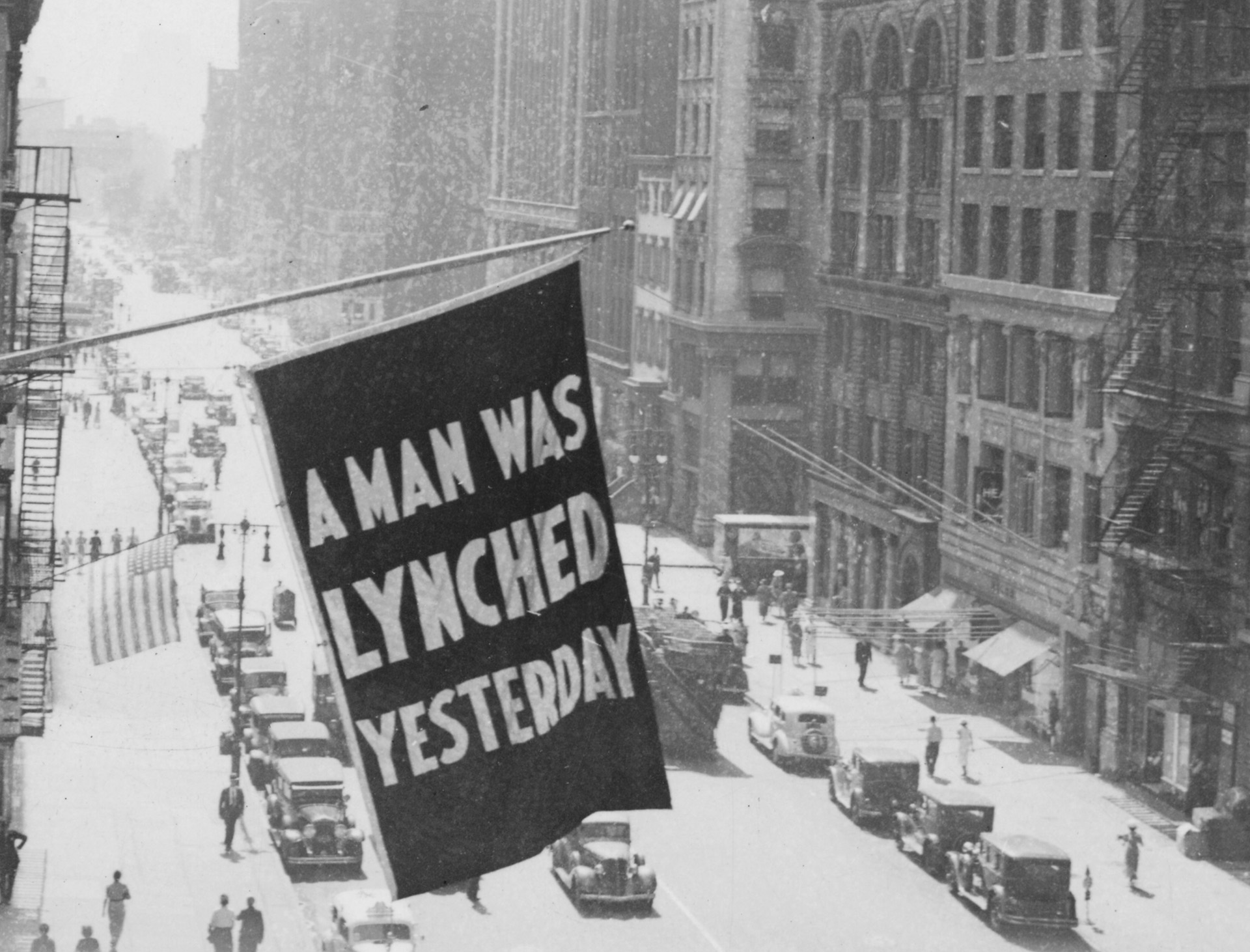

The aftermath dragged on for years. Tensions didn’t dissolve. They hardened. And while government officials made noise about banning lynching, that didn’t exactly stop anything. No one from the mob was ever arrested. No one was held accountable.

But Mary Turner’s name didn’t disappear.

Legacy, Resistance, and the Marker That Refused to Stay Down

Decades later, the courage Mary Turner showed finally started to resonate. In 2008, a group called the Mary Turner Project was founded. Its mission: educate, acknowledge, and try to stitch together what was broken.

They focus on the events of May 1918, and the almost 600 lynchings that took place in Georgia between 1877 and 1950. They raised support to install a historical marker near the site where Mary was murdered. It went up in 2010.

And then someone shot it. Five times.

By 2013, it had to be repaired. Since then, it’s been shot at 27 more times, hit by a vehicle, and completely replaced as recently as 2021.

People tried to erase the truth, just like they tried to erase her. But history has a way of surviving anyway.