Inside the Murder Castle: The True Story of H.H. Holmes and His Killing Factory

In 1893, a pharmacist in Chicago built a hotel specifically designed to kill his guests. He installed gas lines in the bedrooms, secret passages in the walls, and a crematorium in the basement. His victims disappeared during the World's Fair, and their skeletons ended up in medical schools across the country. This is the true story of America's first serial killer.

The Businessman Who Industrialized Murder

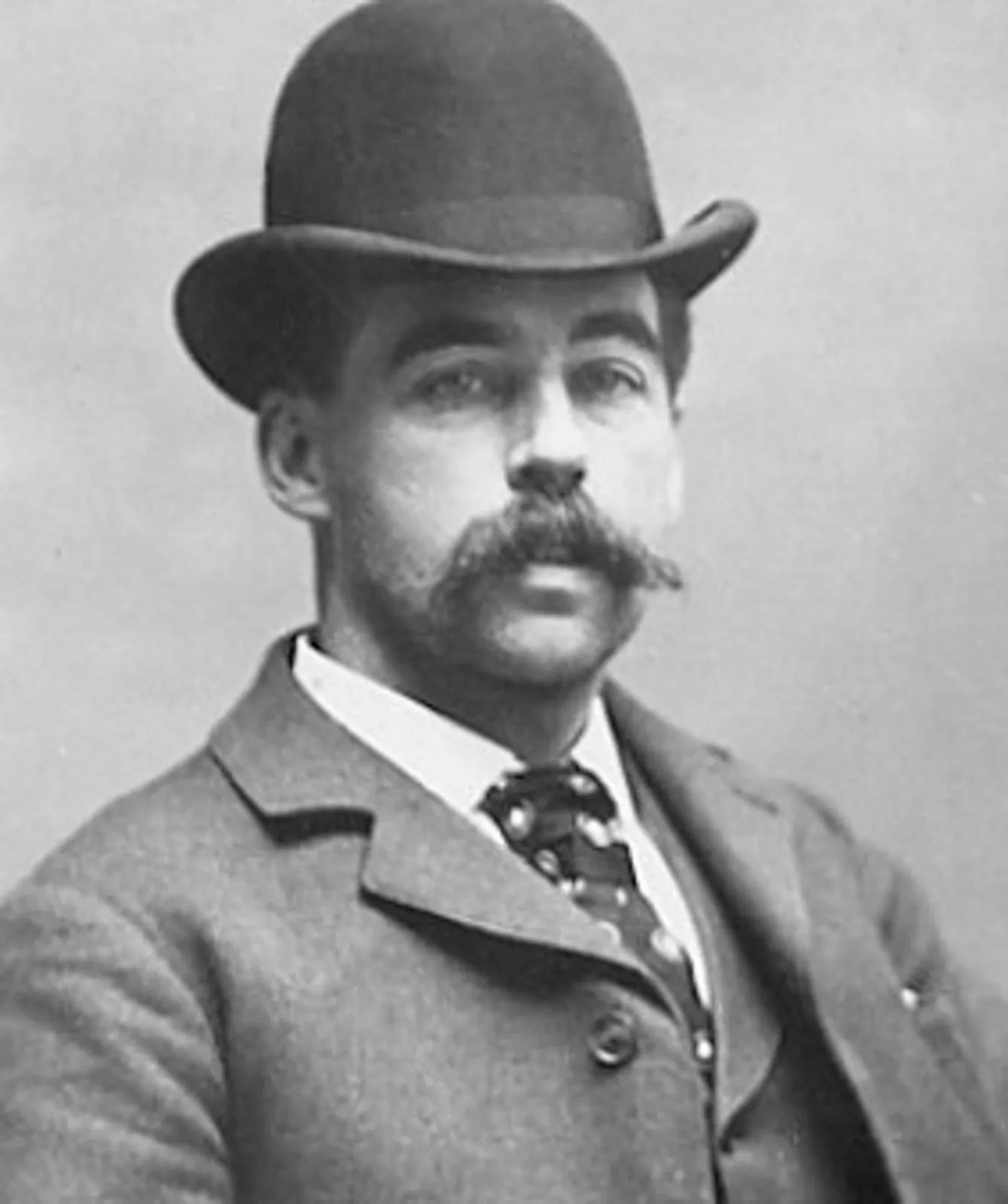

So here's something most people don't know about H.H. Holmes: his real name was Herman Webster Mudgett, and before he became famous for killing people, he was actually really good at stealing furniture.

I know that sounds random, but stay with me because it matters. In 1892, Herman ordered massive amounts of furniture from companies like Tobey Furniture Company. He told them he was buying on behalf of a legitimate business and promised cash on delivery. When the furniture arrived, he accepted it, and then he never paid. When the sheriff showed up with a warrant to recover the stolen goods, the hotel rooms were completely empty. The police were stumped until they bribed a worker, who showed them where everything was hidden: bedroom sets concealed behind fake walls covered with fresh wallpaper, dishes and crockery stuffed into the space above the kitchen ceiling.

This is important because it tells us something about the building that would become known as the Murder Castle. Those hidden rooms and secret passages everyone talks about? They were originally built for fraud, not murder. Herman was a con artist first, and the architecture of his building reflected that. He designed it to hide stolen merchandise, avoid paying contractors, and run insurance scams. The killing came later.

From New Hampshire to Chicago: Building a Monster

Herman Webster Mudgett was born in New Hampshire in 1861. His childhood fits a pattern we see over and over in serial killer cases. He was physically abused at home, had trouble making friends, and showed early signs of cruelty toward animals. Before he turned eleven, he was performing what he called experimental operations on neighborhood pets.

There's one story from his childhood that people always bring up. Some older kids chased him into a doctor's office and forced him to touch a human skeleton. Whether this actually happened the way he described it or not, something clearly connected in his brain between fear, power, and the human body. That connection would define everything he did later.

He went to the University of Michigan Medical School from 1882 to 1884. He didn't finish, but he learned enough anatomy to be dangerous. While he was there, he started stealing cadavers from the labs and reselling them to other medical schools. He also figured out how to run insurance fraud schemes using unidentified bodies. This is where his criminal career actually began: not with murder, but with turning dead bodies into money.

By the time he moved to Chicago, Herman had changed his name to Dr. Henry Howard Holmes. The title gave him authority he hadn't earned, and the new identity helped him escape the trail of fraud charges he'd left behind in other states. He was married to at least three women at the same time, possibly four. Each marriage was part of a con, a way to gain access to money or property or social connections.

The World's Fair Creates the Perfect Hunting Ground

In 1893, Chicago hosted the World's Columbian Exposition, also called the White City. This was a massive event. Over 27 million people visited Chicago that year to see modern inventions like the Ferris wheel, the zipper, and electric lights. The fair transformed the city into a temporary boom town, with thousands of people arriving every day looking for work and housing.

Holmes saw an opportunity. He bought a pharmacy in the Englewood neighborhood from a woman named Mrs. E.S. Holton. Soon after the sale, Mrs. Holton disappeared. Holmes told people she had moved to California. She probably never left the building.

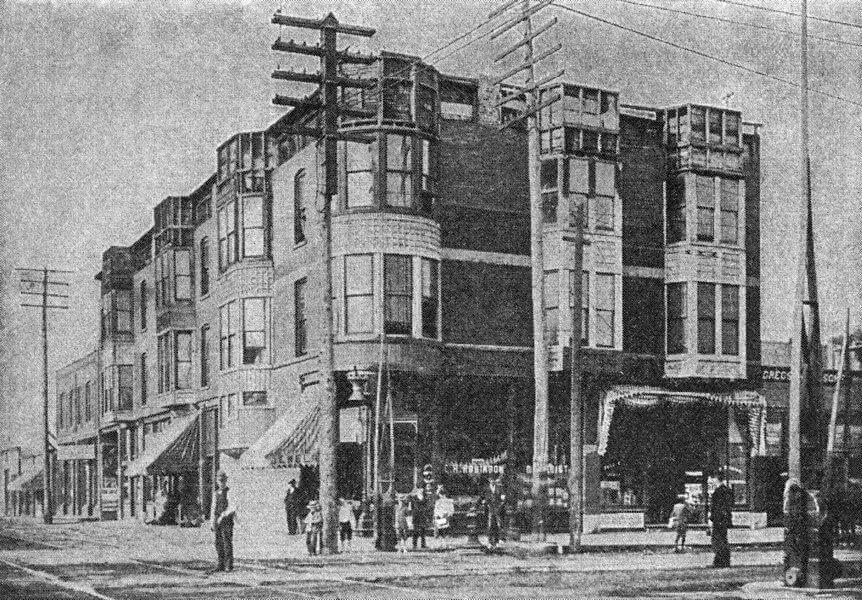

Across the street from the pharmacy, Holmes constructed a three-story mixed-use building. The ground floor had retail shops, and the upper floors were designed as a hotel. He told people he was building it to accommodate World's Fair visitors, which made perfect sense given the housing shortage in the city.

But here's where things get complicated. We know a lot about how this building was constructed because Holmes refused to pay anyone who worked on it. Construction companies sued him, and those lawsuits created a paper trail. An architect named Edward Gallauner even produced detailed diagrams of the building's layout during one of these legal battles. According to these documents, the building started as a legitimate, if fraudulent, business venture.

The transformation into a murder facility happened gradually. Holmes modified the building as he went, adding features that had nothing to do with running a hotel and everything to do with controlling and killing the people inside.

Inside the Factory of Death

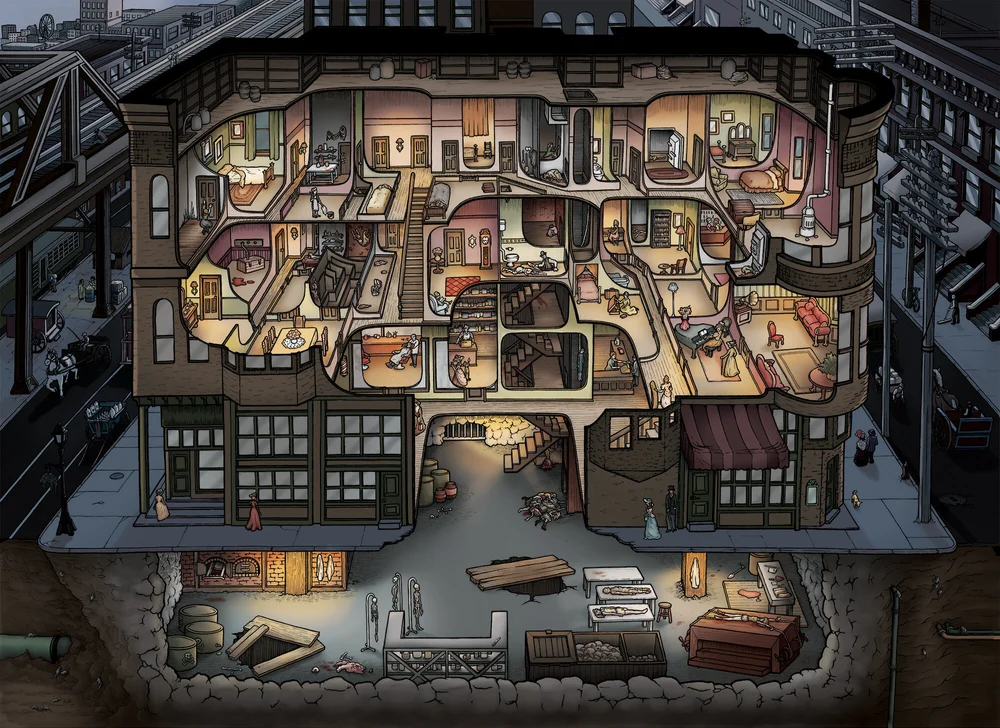

The building had soundproof rooms. Gas lines were installed in some of the guest rooms, controlled by valves in Holmes's private quarters. There were hidden passages that allowed him to move through the building unseen, and peepholes where he could watch his guests. The building had chutes that dropped from the upper floors down to the basement.

The basement is where the real horror happened. Police found a dissection table down there, along with massive vats that Holmes had used to dissolve bodies in acid. There was an eight-foot-tall iron stove that looked like an oil furnace but was actually used as a crematorium. Holmes would strip flesh from bones using the acid, burn what remained in the furnace, and then clean and articulate the skeletons. He sold them to medical schools.

Think about that for a second. He wasn't killing people in a frenzy. He was processing them. He had a system: trap them in the soundproof rooms, kill them with gas, drop them down the chute to the basement, dissolve the tissue, burn the evidence, and sell whatever was left. This was industrialized murder.

Now, I have to mention this because it's important for accuracy: a lot of what people believe about the Murder Castle is exaggerated. The torture equipment, the elaborate medieval dungeon aesthetic, most of that came from newspapers in the 1940s, not from the original police investigation in the 1890s. The real building was horrifying enough without the added mythology. The gas chambers were real. The acid vats were real. The crematorium was real. But Holmes wasn't stretching people on racks or building iron maidens. He was running an efficient, profitable murder operation, and that's somehow more disturbing than the Gothic fantasy version.

|

The Victims We Know About

Figuring out exactly how many people Holmes killed is basically impossible. He confessed to 27 murders at first, then later changed his story and claimed more than 130. Newspapers at the time speculated he'd killed 200 people. Modern historians think the real number is somewhere between nine confirmed victims and maybe fifty total.

The victims we can confirm are mostly connected to his financial crimes. Mrs. Holton, the woman who sold him the pharmacy, was probably his first victim in Chicago. Julia Conner and her daughter Pearl disappeared after Julia's husband, who ran a jewelry counter in Holmes's store, left town. Minnie Williams and her sister Nannie both vanished after Holmes married Minnie and gained control of her property. Emeline Cigrand, one of his mistresses, disappeared as well.

But the case that actually got him caught was the murder of Benjamin Pitezel and three of Pitezel's children. Holmes convinced Pitezel to fake his own death for a ten thousand dollar insurance payout. Then Holmes actually killed him and collected the money. To cover his tracks, he murdered three of Pitezel's children in three different states: Indiana, Illinois, and Ontario, Canada.

This was the crime that finally brought him down. A detective named Frank Geyer tracked the murders across state lines and arrested Holmes in 1894. The insurance fraud was too big, too spread out, too complicated to hide.

The Media Makes a Monster

Holmes's trial happened at the peak of Yellow Journalism in America. Publishers like Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst were competing for newspaper sales by printing the most sensational, shocking stories they could find. Holmes was perfect for them.

They called him the Beast of Chicago. The Torture Doctor. The Devil in the White City. They printed wild, unverified claims about his crimes, many of which came directly from Holmes himself, who loved the attention and kept changing his story to make himself sound more notorious. He told reporters he'd suffocated people in vaults, boiled a man in oil, poisoned wealthy women. Some of this might have been true. A lot of it probably wasn't.

The newspapers didn't care about accuracy. They cared about circulation. And Holmes, being a narcissist who craved infamy, was happy to give them whatever they wanted.

There's even a persistent theory that Holmes was also Jack the Ripper. The timeline sort of works. Holmes had medical training, and Jack the Ripper's murders showed anatomical knowledge. Some handwriting analysts claim Holmes's writing matches letters supposedly written by the Ripper. Holmes's great-great-grandson has publicly argued that his ancestor was in London during the Whitechapel murders.

Most historians dismiss this theory as wishful thinking. People want to connect two famous killers into one ultimate boogeyman. But there's no solid evidence that Herman Mudgett was ever in London, and the theory mostly exists because it makes for a good story.

Death and the Final Con

Holmes was executed by hanging on May 7, 1896, in Philadelphia. He was 34 years old. He'd been convicted of murdering Benjamin Pitezel, although everyone knew he'd killed far more people than that.

According to witnesses, he was calm at the execution. He didn't seem afraid or remorseful. Right before he died, he recanted his confession and claimed he'd only killed five people, which was obviously a lie. Even on the gallows, he was still running a con, still trying to control his own narrative.

But here's the wildest part of the whole story. Holmes left very specific instructions for his burial. He wanted to be placed in a pine coffin, and then he wanted that coffin filled completely with cement. The heavy coffin was supposed to be buried ten feet underground and covered with more cement.

Why would he do this? Because he was terrified someone would steal his corpse.

Holmes had spent years stealing bodies, cutting them apart, and selling them to medical schools. He made money by turning human remains into commodities. And he knew exactly how that system worked because he'd built part of it himself. So he was absolutely paranoid that someone would dig him up, dissect him, and sell his skeleton the same way he'd done to his victims.

The irony is almost too perfect. The man who annihilated other people's identities, who reduced them to anonymous specimens in medical school display cases, died terrified of the same fate. He fought harder to preserve his own corpse than he ever did to preserve anyone else's life.

Even after this incredibly secure burial, rumors spread that Holmes had somehow faked his execution and escaped. People claimed he'd bribed officials to hang another prisoner in his place. These stories persisted for decades, which tells you something about how Holmes was perceived. People genuinely believed he was capable of conning the entire criminal justice system, even from inside a prison cell, even facing execution.

What We're Left With

The story of H.H. Holmes is fundamentally a story about the commercialization of death. Herman Mudgett learned in medical school that bodies had value, and he spent the rest of his life exploiting that knowledge. He built a business model around fraud, murder, and corpse disposal. The Murder Castle was a factory, and human beings were the product.

Was he America's first serial killer? Probably not. There were certainly other killers operating before him. But he might have been the first to industrialize it, to create systems and infrastructure specifically designed for repeated, profitable murder.

The legend of H.H. Holmes is bigger than the reality, but the reality is bad enough. Nine confirmed victims, maybe fifty total, processed through a building in Chicago that started as a real estate scam and evolved into something much worse. The man who built it died cemented into the ground, finally anonymous and immobile, exactly what he'd feared most.

Sign up for the 10 Minute Murder newsletter